Many of us think of world building as a necessary chore to give your writing a decent setting. It doesn’t have to be like that.

Building worlds is a wonderful inspiration to write and a rewarding pastime in itself. In this post, we’ll show you how to start, and why it’s worth the effort.

Scale Isn’t Important

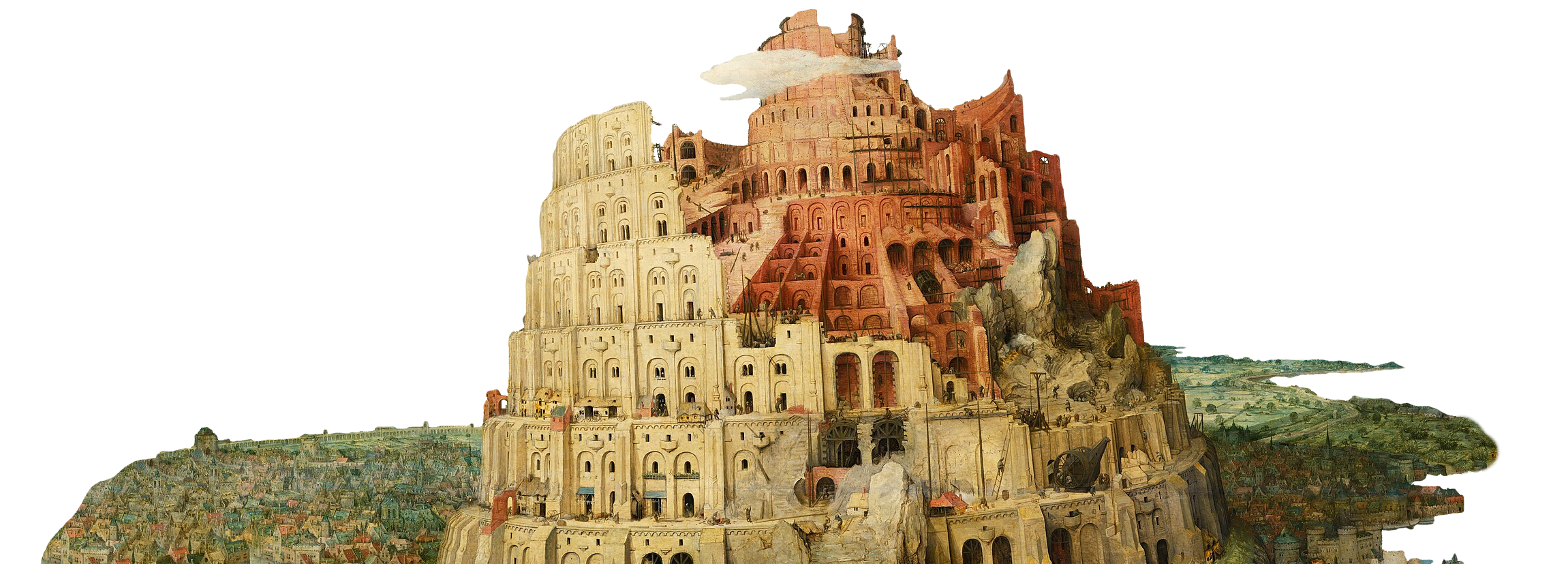

When we think of world building, we often think of the classics that inhabit a sci-fi or fantasy setting: Lord of the Rings, Dune, Star Trek, Harry Potter, Star Wars, even Mad Max. These are all big worlds with many cultures, technologies, and deep histories. We see a lot of worlds like that.

But your world doesn’t need to be big to matter. A world could be a droplet of water that was born in a raincloud and ends when it evaporates on a rock somewhere in Tasmania. It could be the size of a pinhead, its lifespan measured in minutes. Empires can rise and fall in seconds. A love story could be over in a nanosecond.

We needn’t be that extreme. A world could be a lazy river and a forest inhabited by a few animals. That’s The Wind in the Willows, a simple, charming world loved by millions. So scale is not important. Nor is complexity. You just need to take the time.

Time and Again

How you use time in your world depends on what you want to do with it. For example, if you want to use your world to tell a story, it probably needs linear time because most stories have a beginning and an end. Without time, nothing happens or changes.

There’s time travel too, of course. It’s an over-used idea and not as interesting as it used to be, but you can still have fun with it. Your world could even have time flowing in reverse. Or multiple time streams. It’s not easy, but it can be done if you want to create multiple linked, mind-bending narratives.

Just Give Me Some Space

Your world may need a physical space of some kind. True, you could build a world with a bunch of ghosts who live nowhere and do nothing—but that’s really just a static image, a two-dimensional portrait. We’re physical apes that evolved inside space and time. That’s our home and what we understand—so most of our stories live there too.

Take a tree in your backyard. A lot happens in a tree: you have weather, seasons, owls, sparrows, moths, nests, fungi, squirrels, children and their treehouse, and the evil neighbor who wants to trim the branches. A tree is a world. Sometimes simple is better.

Enter Stage Left (or not)

What about characters, entities with motives? Most characters are searching for something they don’t have but want, and try to do something about getting it. Love. Power. Fame. Your characters could be super-intelligent trans-dimensional gods. Gods may be powerful but above all don’t want to be forgotten—that’s a motive right there. Ants want to protect their queen. Maybe rats worship the God of Gnaw, or perhaps they want to better themselves. Remember The Secret of Nimh?

A caveat: We assume that all worlds must have characters, but that’s not necessarily true. You don’t need characters to create interesting worlds. The deepest Amazon is a world, a vast, intricate ecosystem brimming with organisms. A beautiful, complex forest doesn’t need motives other than to exist.

Choose Your Kernel

So where to begin? Choose a kernel of interest and build around that. See where it takes you. You could start with a place you find interesting: a forgotten museum, or a cave you visited as a child. Or the Mariana Trench. We don’t know much about the deep ocean, but we do know it’s haunted by scary deep sea creatures. What other creatures could live down there? Could some of them be intelligent, like from The Abyss?

Or start by choosing a time period. How about the court of Louis XIV? Perhaps he gets a surprise visit from aliens wearing 10-dimensional wigs. Instant fun. How about the Cambrian Explosion half a billion years ago, where evolution went mad and anything seemed possible?

Lots of people choose our galaxy as a setting. Most SF authors do. Others choose our shared myths as their inspiration—like many fantasy authors. Old myths and ideas stick because they reach deep into our collective past. That’s fine too, but try to add a new angle. Something fresh.

Moths vs Butterflies?

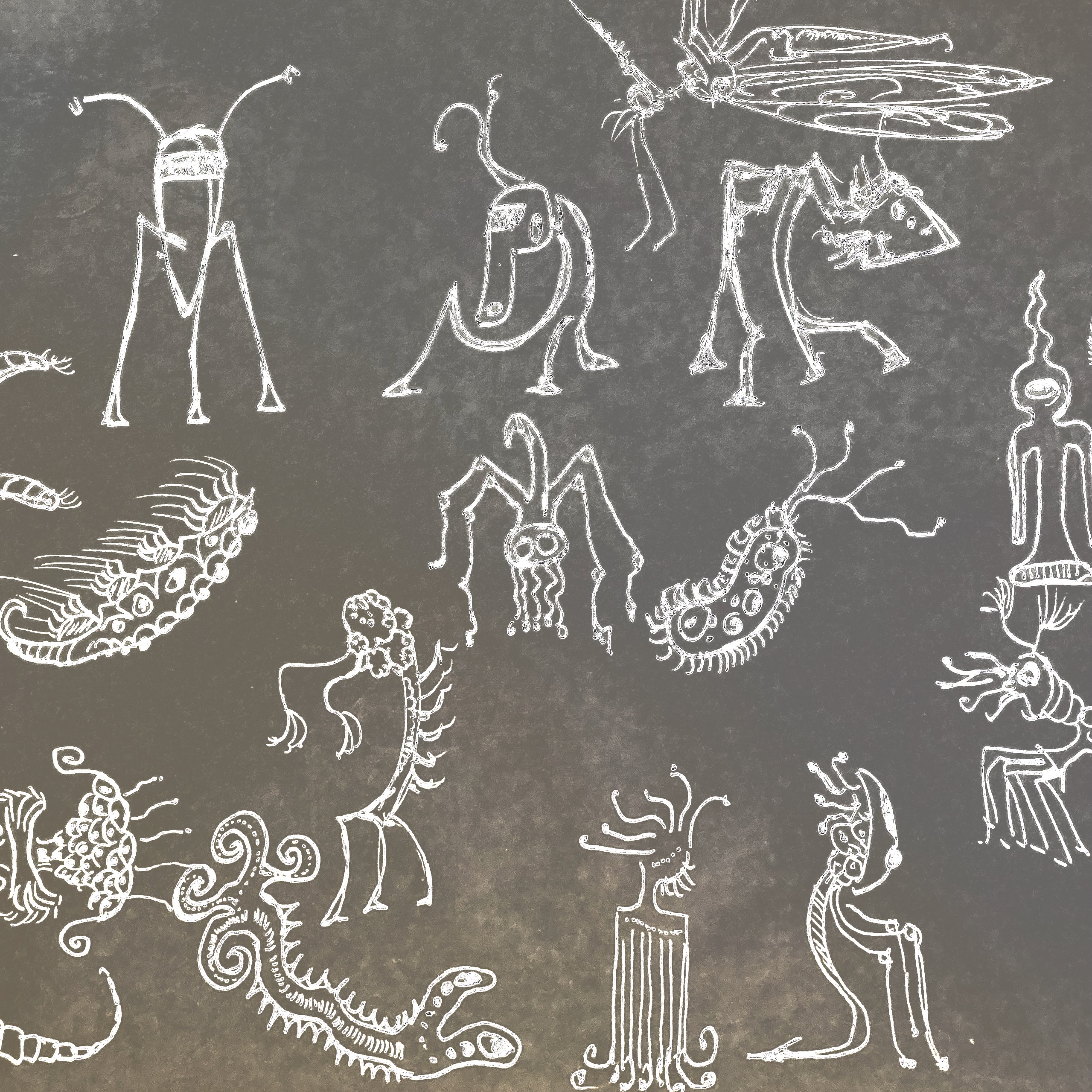

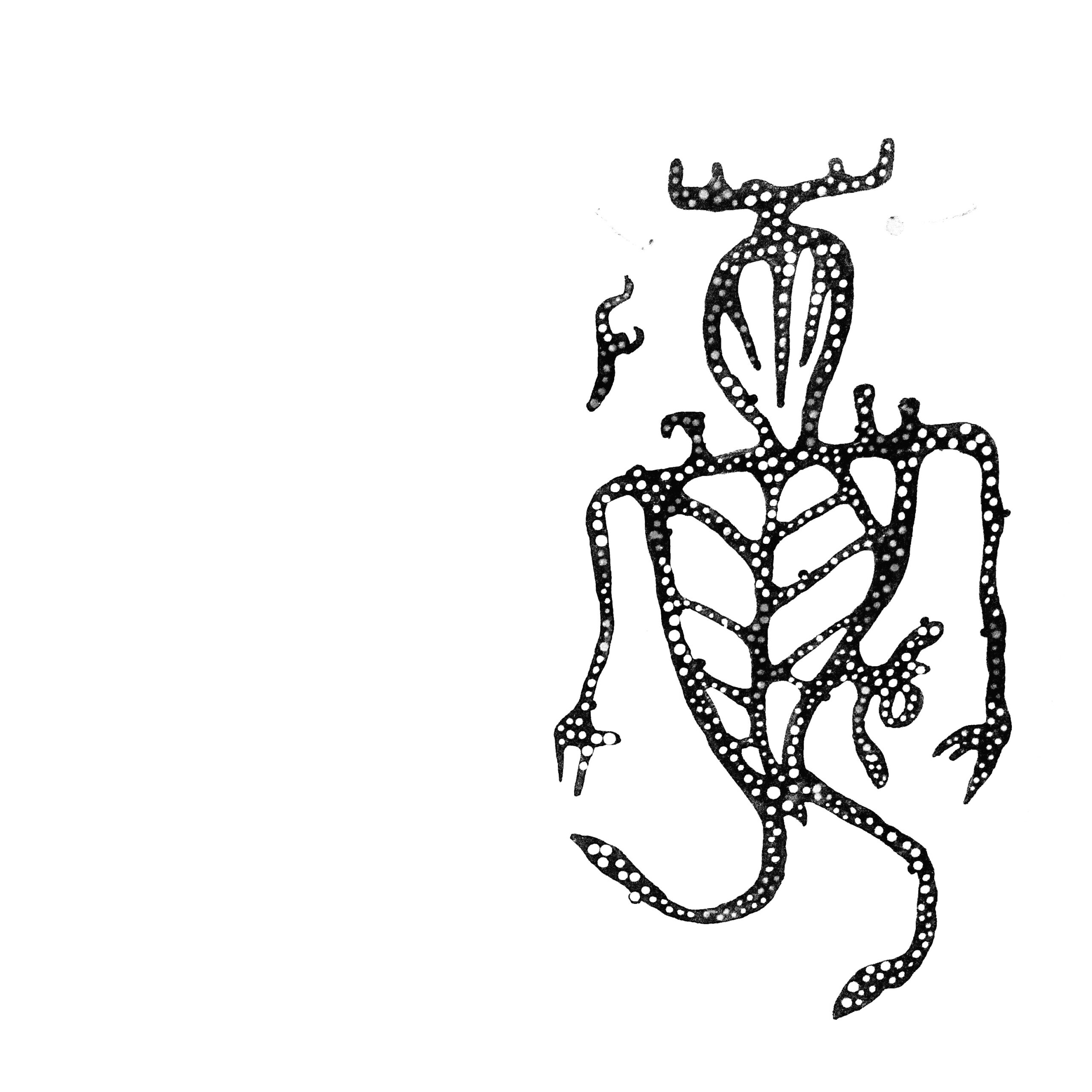

So far we’ve covered time- and location-based kernels for your world’s setting. But you could start building your world by choosing an organism.

For example, if you love butterflies, build a world that’s full of them. All kinds. Describe them. Draw them. Create family trees of butterflies. Maybe these butterflies are different from ours. Maybe they have six or eight wings.

Next, think about what butterflies want. Many humans are obsessed with being beautiful and being adored by other humans. Maybe that’s true for butterflies too. In your world, every butterfly could be a Kardashian. That sounds like a dystopian butterfly world. Well, why not?

What about social structures? Does your butterfly world have a King of Wings? Or a religious messiah? How would they rule, and what would they preach? And try to come up with a point of conflict to create tension. For example, do moths exist in butterfly world? Are they friends, or mortal foes—light versus dark?

But don’t worry about scale. Bigger isn’t better—remember The Wind in the Willows. Complexity doesn’t automatically mean more interesting. Look for depth. Relationships. Meaning. Interest. It doesn’t even need to make sense.

How to Build Worlds

You don’t need much of an imagination to build worlds, but it helps. The fact is we can’t imagine anything in a vacuum. We’re not smart enough for that yet. Everything we dream up is at least partially borrowed from somebody else, from endless generations of recorded knowledge.

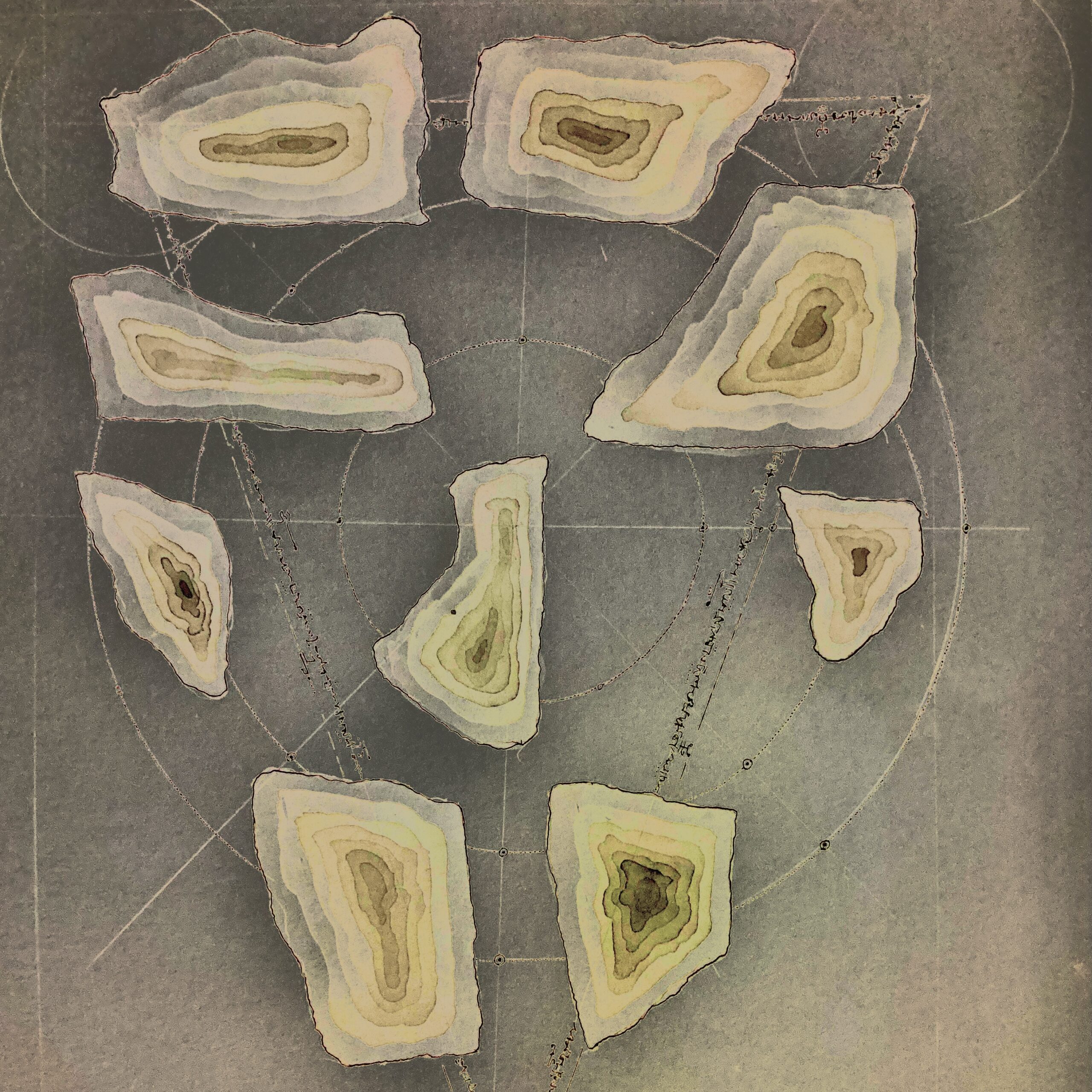

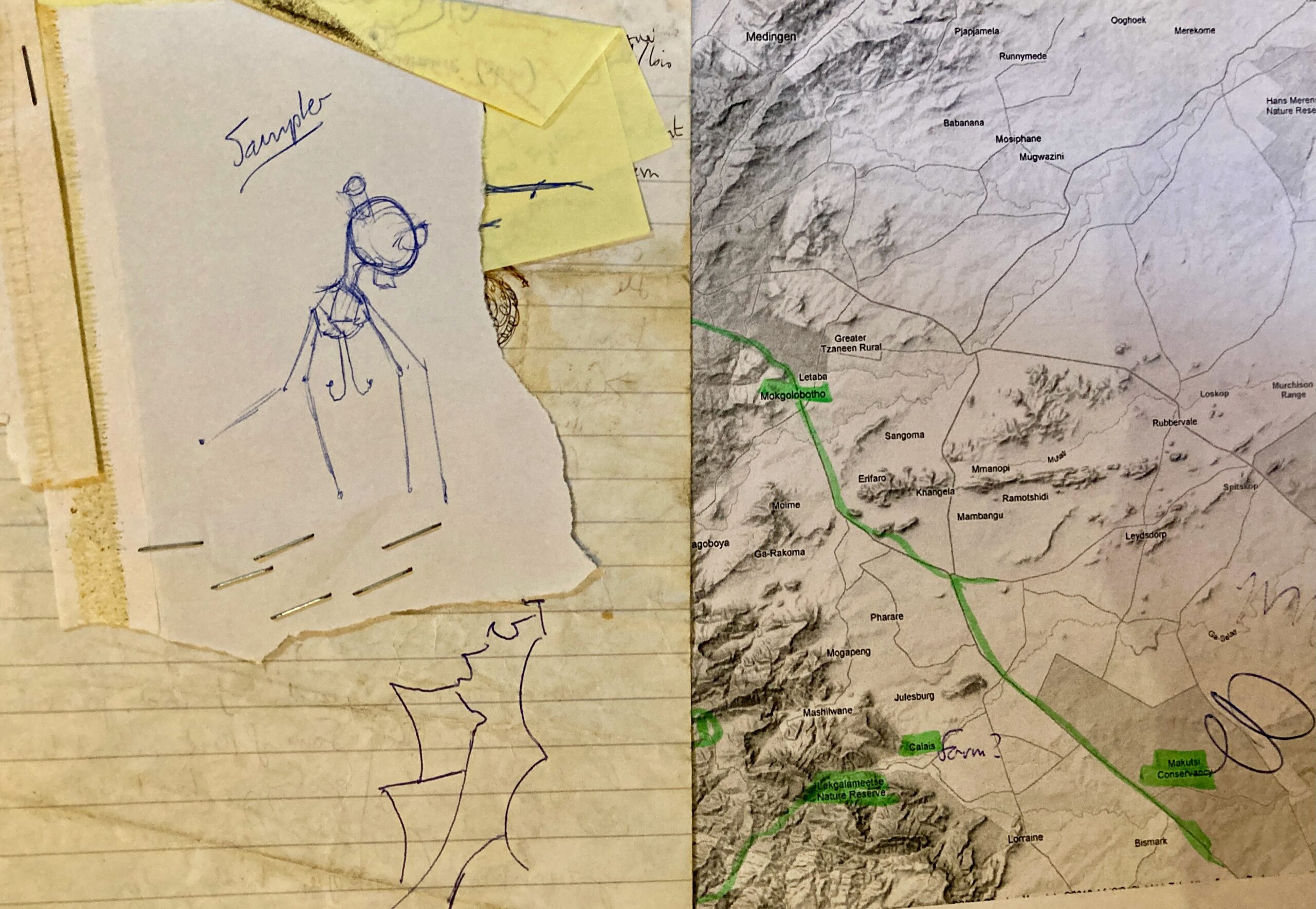

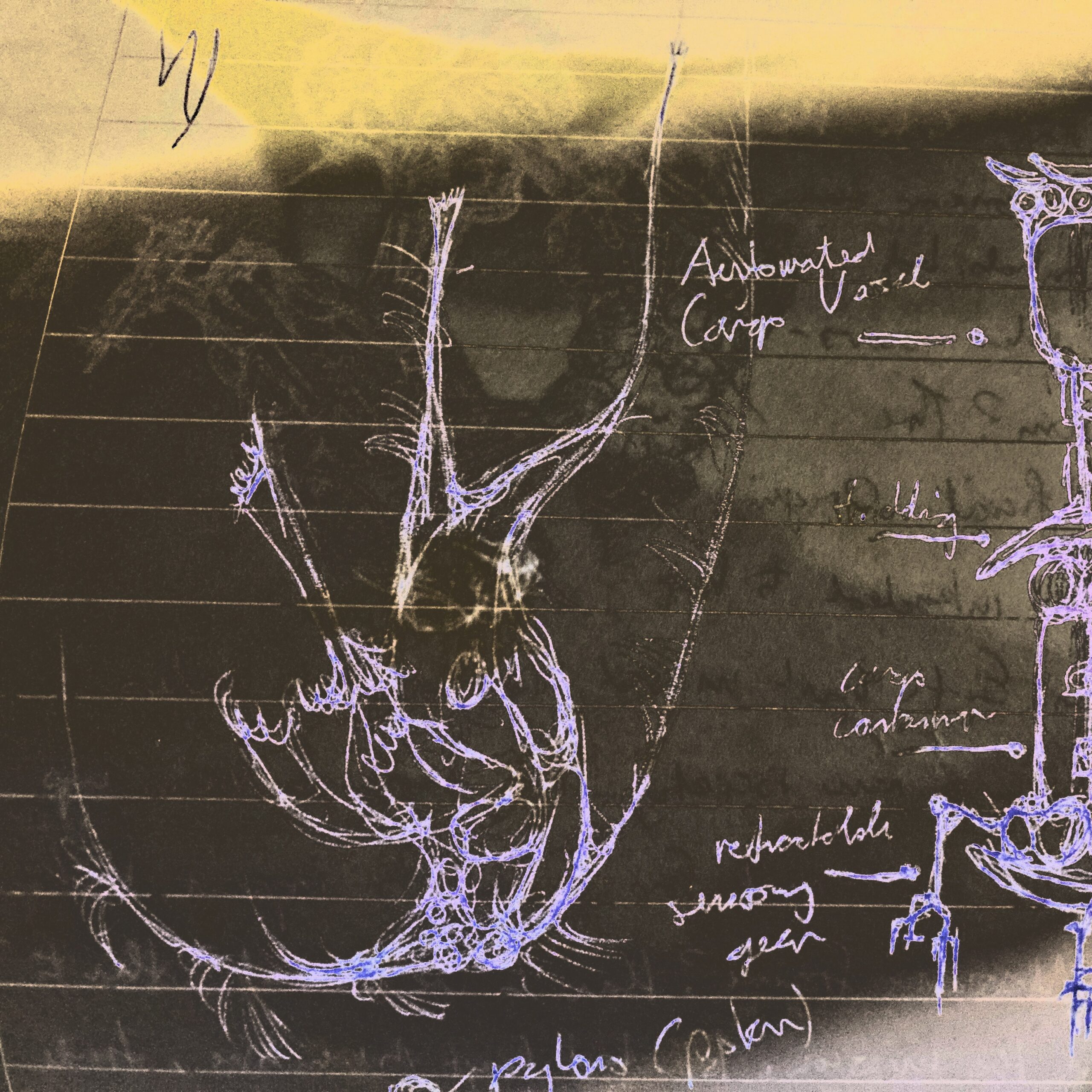

But that doesn’t mean you can’t get creative. Observe what interests you. Record it, even the small, seemingly boring things—because you often need that to make your world interesting and granular. When you have an idea, use whatever you like or what’s nearby to record it. Your world could consist entirely of pictures you draw, notes you make, or even a giant spreadsheet. Also try mind maps, which are useful for connecting ideas.

You have a phone. You may love or hate it, but it’s usually close by. Use something like Google Keep to make notes. Or Post-it notes. Paper and ink. The humble Notepad app you’ll find on any Windows computer. Decide later what you want to do with those notes. Just record it. Get it down somehow, somewhere.

Once you’ve recorded some ideas, start messing with them:

Connect

Try to find ways to link the things and organisms that live in your worlds, even if they repel each other. Draw diagrams to show those relationships.

Invert

Take the ordinary and turn it inside out. Flip them over. For example, what if robots invented humans—something Stanislaw Lem explored in his Cyberiad? Would robots be amazed at how humans can answer questions, just like our ChatGTP? But is it worth spending billions on farms to power/feed these fleshy things? In the inverted world, humans are not intelligent—they’re blindly copying, biological algorithms that scrape existing robot knowledge.

Distort

Distort what you see. Pull at it. Twist it out of shape. What happens in a world where you could legally erase your child until it is 20? What kind of story would those kids have to tell when they flee the erasure? Where would they hide? How would they live?

Why Bother?

It may not be obvious. Why should a grown up bother building worlds? What’s the point? Who cares? Some days you may not have a good answer.

But once you get into it, you somehow always come back because it’s a great place, a home, a mental place where you can just dream things up. World building is where you go to play when adulting gets too hard. And yes, they will inspire you to write stories. But even if you’re not a writer, there are at least three good reasons to build worlds:

Learn & Do New Stuff

When you’re building worlds you’ll discover, learn, and do new things. You may, for example, learned a lot about entomology—the study of insects—when you write a book that takes place in a weird tropical place with lots of species.

Over time you may learn how to make spaceships and aliens using software. You may learn about artificial language and create a new alphabet based on Edison’s visible speech concept. When you build worlds, you learn things—and that’s good!

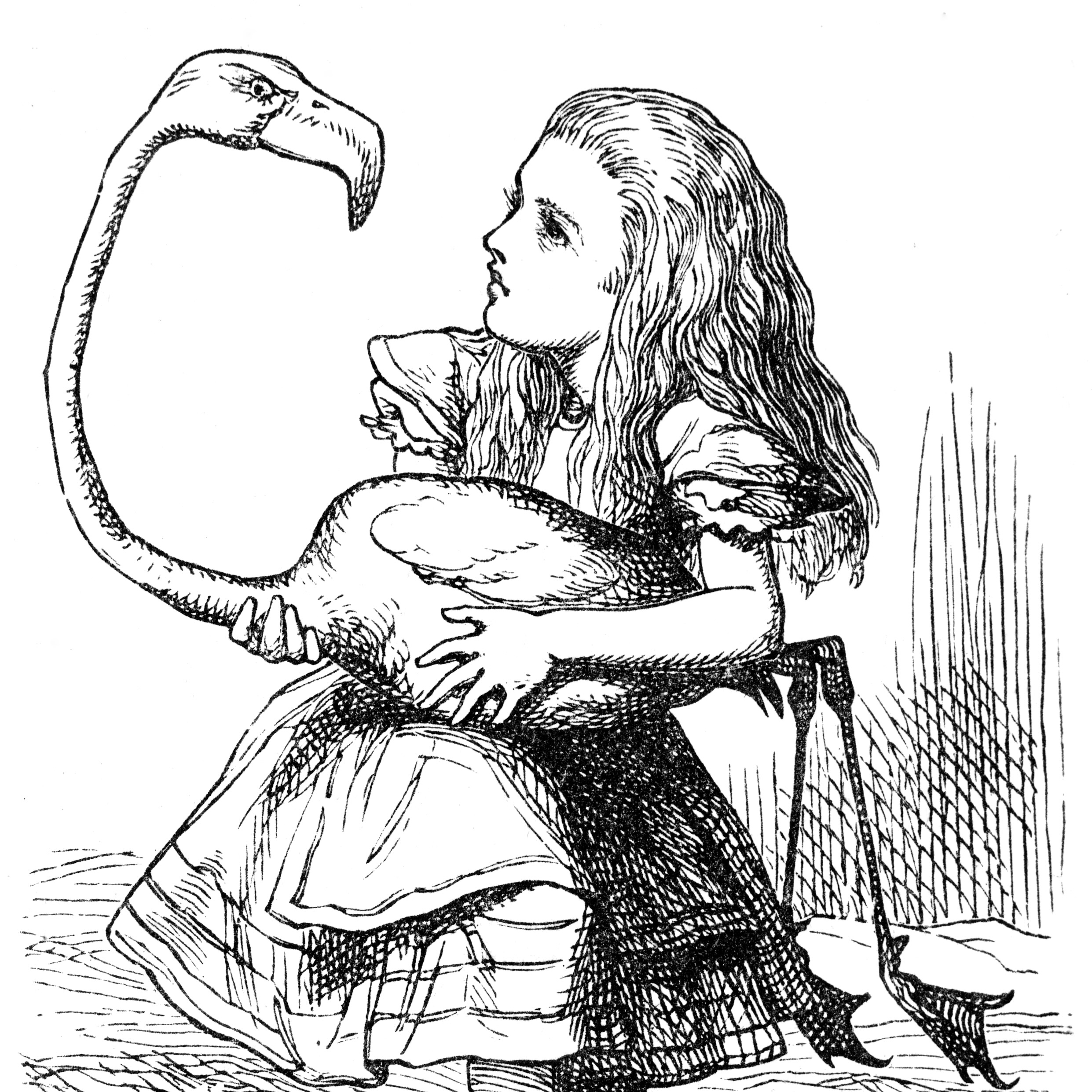

Make Somebody Happy

You can use world building to write books—but that usually comes after you built the world. The stories come later. If you use your world to create and sell stories, you could make millions of people happy. Or just one person. The Hobbit and Alice in Wonderland exist because they’re children’s stories. Tolkien and Lewis Carroll weren’t trying to make money when they wrote their stories—they wrote them to make somebody happy.

It’s Fun!

People talk a lot about sandbox worlds, mostly in gaming. But even those hyper-cool universes have limits that somebody else created. You can inhabit their worlds. You can even build wacky structures on them, or share it with your friends. But it doesn’t belong to you. You need to play by the creator’s rules. Use their toolset. Always. There’s no such thing as freedom in somebody else’s world you’re visiting. Chances are you’re just a paying guest.

And that’s why world building is fun. Because it’s yours. It belongs to you forever, and you can use it any way you want. Nobody can tell you what to do with it. There are no limits in your worlds. You decide what’s important, what makes you smile.