Should you use gestures while you’re presenting? What about facial expressions? Find out in The Truth about Gesture, a chapter from Dale Carnegie The Art of Public Speaking (1915).

Public speaking advice drowns us in rules about where to place your hands, how to move your feet, or when to raise your eyebrows. Carnegie takes a different route. He reminds us that authentic expression doesn’t begin with the body. It begins with conviction. Gestures that matter aren’t calculated, but felt.

In this vivid and still-relevant chapter, he cuts through the artificiality and urges speakers to focus on thought, presence, and purpose, not choreography. What follows is not a manual of movements, but a challenge to speak with your whole being.

The Truth about Gesture, in: The Art of Public Speaking (1915), by Dale Carnegie

Gesture is really a simple matter that requires observation and common sense rather than a book of rules. Gesture is an outward expression of an inward condition. It is merely an effect—the effect of a mental or an emotional impulse struggling for expression through physical avenues.

You must not, however, begin at the wrong end: if you are troubled by your gestures, or a lack of gestures, attend to the cause, not the effect. It will not in the least help matters to tack on to your delivery a few mechanical movements. If the tree in your front yard is not growing to suit you, fertilize and water the soil and let the tree have sunshine. Obviously it will not help your tree to nail on a few branches. If your cistern is dry, wait until it rains; or bore a well. Why plunge a pump into a dry hole?

The speaker whose thoughts and emotions are welling within him like a mountain spring will not have much trouble to make gestures; it will be merely a question of properly directing them. If his enthusiasm for his subject is not such as to give him a natural impulse for dramatic action, it will avail nothing to furnish him with a long list of rules. He may tack on some movements, but they will look like the wilted branches nailed to a tree to simulate life. Gestures must be born, not built. A wooden horse may amuse the children, but it takes a live one to go somewhere.

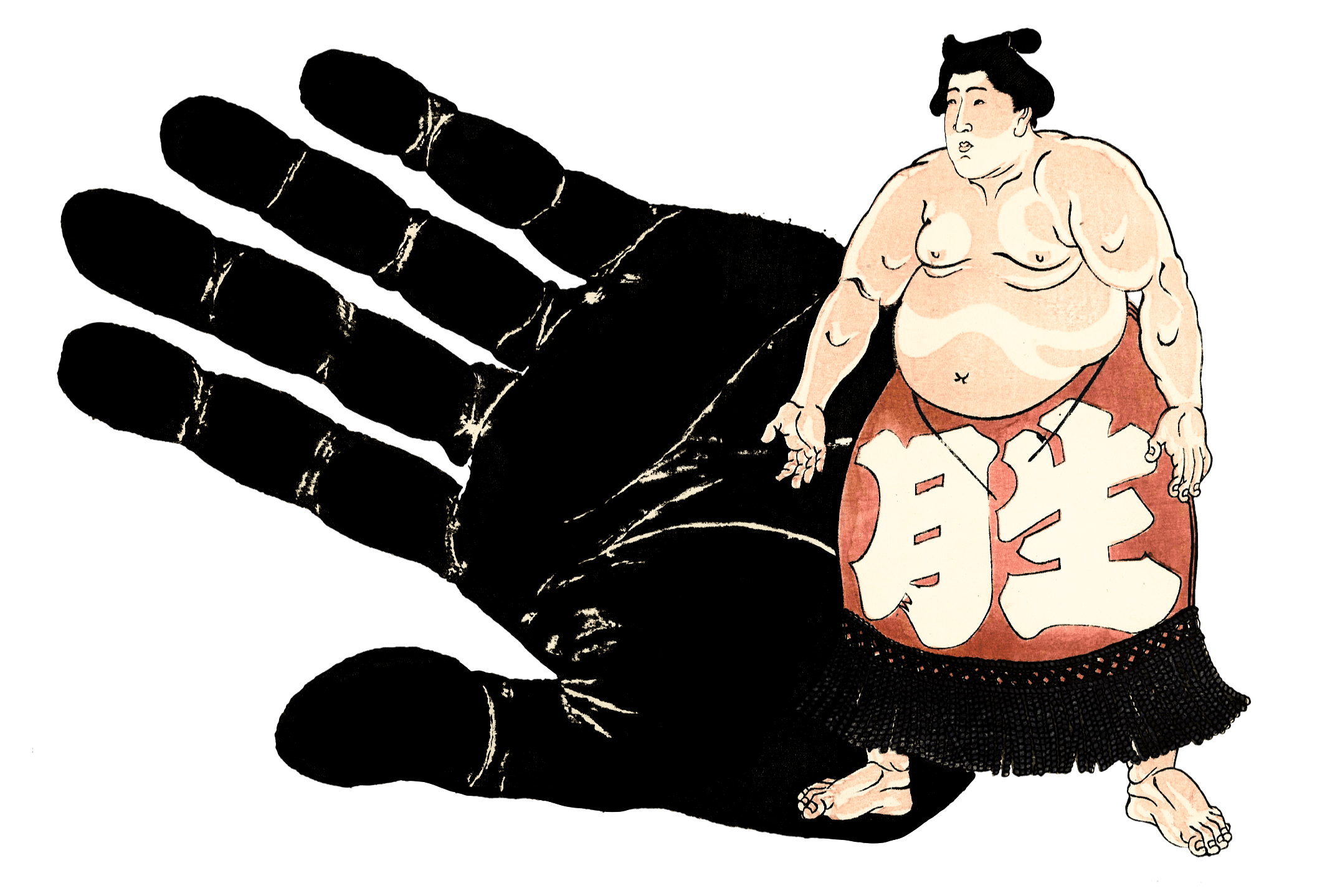

It is not only impossible to lay down definite rules on this subject, but it would be silly to try, for everything depends on the speech, the occasion, the personality and feelings of the speaker, and the attitude of the audience. It is easy enough to forecast the result of multiplying seven by six, but it is impossible to tell any man what kind of gestures he will be impelled to use when he wishes to show his earnestness. We may tell him that many speakers close the hand, with the exception of the forefinger, and pointing that finger straight at the audience pour out their thoughts like a volley; or that others stamp one foot for emphasis; or that Mr. Bryan often slaps his hands together for great force, holding one palm upward in an easy manner; or that Gladstone would sometimes make a rush at the clerk’s table in Parliament and smite it with his hand so forcefully that Disraeli once brought down the house by grimly congratulating himself that such a barrier stood between himself and “the honorable gentleman.”

All these things, and a bookful more, may we tell the speaker, but we cannot know whether he can use these gestures or not, any more than we can decide whether he could wear Mr. Bryan’s clothes. The best that can be done on this subject is to offer a few practical suggestions, and let personal good taste decide as to where effective dramatic action ends and extravagant motion begins.

Any gesture that merely calls attention to itself is bad

The purpose of a gesture is to carry your thought and feeling into the minds and hearts of your hearers; this it does by emphasizing your message, by interpreting it, by expressing it in action, by striking its tone in either a physically descriptive, a suggestive, or a typical gesture—and let it be remembered all the time that gesture includes all physical movement, from facial expression and the tossing of the head to the expressive movements of hand and foot. A shifting of the pose may be a most effective gesture.

What is true of gesture is true of all life. If the people on the street turn around and watch your walk, your walk is more important than you are—change it. If the attention of your audience is called to your gestures, they are not convincing, because they appear to be—what they have a doubtful right to be in reality—studied. Have you ever seen a speaker use such grotesque gesticulations that you were fascinated by their frenzy of oddity, but could not follow his thought? Do not smother ideas with gymnastics. Savonarola would rush down from the high pulpit among the congregation in the duomo at Florence and carry the fire of conviction to his hearers; Billy Sunday slides to base on the platform carpet in dramatizing one of his baseball illustrations. Yet in both instances the message has somehow stood out bigger than the gesture—it is chiefly in calm afterthought that men have remembered the form of dramatic expression. When Sir Henry Irving made his famous exit as “Shylock” the last thing the audience saw was his pallid, avaricious hand extended skinny and claw-like against the background. At the time, every one was overwhelmed by the tremendous typical quality of this gesture; now, we have time to think of its art, and discuss its realistic power.

Only when gesture is subordinated to the absorbing importance of the idea—a spontaneous, living expression of living truth—is it justifiable at all; and when it is remembered for itself—as a piece of unusual physical energy or as a poem of grace—it is a dead failure as dramatic expression. There is a place for a unique style of walking—it is the circus or the cake-walk; there is a place for surprisingly rhythmical evolutions of arms and legs—it is on the dance floor or the stage. Don’t let your agility and grace put your thoughts out of business.

One of the present writers took his first lessons in gesture from a certain college president who knew far more about what had happened at the Diet of Worms than he did about how to express himself in action. His instructions were to start the movement on a certain word, continue it on a precise curve, and unfold the fingers at the conclusion, ending with the forefinger—just so. Plenty, and more than plenty, has been published on this subject, giving just such silly directions. Gesture is a thing of mentality and feeling—not a matter of geometry. Remember, whenever a pair of shoes, a method of pronunciation, or a gesture calls attention to itself, it is bad. When you have made really good gestures in a good speech your hearers will not go away saying, “What beautiful gestures he made!” but they will say, “I’ll vote for that measure.” “He is right—I believe in that.”

Gestures should be born of the moment

The best actors and public speakers rarely know in advance what gestures they are going to make. They make one gesture on certain words tonight, and none at all tomorrow night at the same point—their various moods and interpretations govern their gestures. It is all a matter of impulse and intelligent feeling with them—don’t overlook that word intelligent. Nature does not always provide the same kind of sunsets or snowflakes, and the movements of a good speaker vary almost as much as the creations of nature.

Now all this is not to say that you must not take some thought for your gestures. If that were meant, why this chapter? When the sergeant despairingly besought the recruit in the awkward squad to step out and look at himself, he gave splendid advice—and worthy of personal application. Particularly while you are in the learning days of public speaking you must learn to criticise your own gestures. Recall them—see where they were useless, crude, awkward, what not, and do better next time. There is a vast deal of difference between being conscious of self and being self-conscious.

It will require your nice discrimination in order to cultivate spontaneous gestures and yet give due attention to practice. While you depend upon the moment it is vital to remember that only a dramatic genius can effectively accomplish such feats as we have related of Whitefield, Savonarola, and others: and doubtless the first time they were used they came in a burst of spontaneous feeling, yet Whitefield declared that not until he had delivered a sermon forty times was its delivery perfected. What spontaneity initiates let practice complete. Every effective speaker and every vivid actor has observed, considered and practiced gesture until his dramatic actions are a sub-conscious possession, just like his ability to pronounce correctly without especially concentrating his thought. Every able platform man has possessed himself of a dozen ways in which he might depict in gesture any given emotion; in fact, the means for such expression are endless—and this is precisely why it is both useless and harmful to make a chart of gestures and enforce them as the ideals of what may be used to express this or that feeling. Practice descriptive, suggestive, and typical movements until they come as naturally as a good articulation; and rarely forecast the gestures you will use at a given moment: leave something to that moment.

Avoid monotony in gesture

Roast beef is an excellent dish, but it would be terrible as an exclusive diet. No matter how effective one gesture is, do not overwork it. Put variety in your actions. Monotony will destroy all beauty and power. The pump handle makes one effective gesture, and on hot days that one is very eloquent, but it has its limitations.

Any movement that is not significant, weakens

Do not forget that. Restlessness is not expression. A great many useless movements will only take the attention of the audience from what you are saying. A widely-noted man introduced the speaker of the evening one Sunday lately to a New York audience. The only thing remembered about that introductory speech is that the speaker played nervously with the covering of the table as he talked. We naturally watch moving objects. A janitor putting down a window can take the attention of the hearers from Mr. Roosevelt. By making a few movements at one side of the stage a chorus girl may draw the interest of the spectators from a big scene between the “leads.” When our forefathers lived in caves they had to watch moving objects, for movements meant danger. We have not yet overcome the habit. Advertisers have taken advantage of it—witness the moving electric light signs in any city. A shrewd speaker will respect this law and conserve the attention of his audience by eliminating all unnecessary movements.

Gesture should either be simultaneous with or precede the words—not follow them

Lady Macbeth says: “Bear welcome in your eye, your hand, your tongue.” Reverse this order and you get comedy. Say, “There he goes,” pointing at him after you have finished your words, and see if the result is not comical.

Do not make short, jerky movements

Some speakers seem to be imitating a waiter who has failed to get a tip. Let your movements be easy, and from the shoulder, as a rule, rather than from the elbow. But do not go to the other extreme and make too many flowing motions—that savors of the lackadaisical.

Put a little “punch” and life into your gestures. You can not, however, do this mechanically. The audience will detect it if you do. They may not know just what is wrong, but the gesture will have a false appearance to them.

Facial expression is important

Have you ever stopped in front of a Broadway theater and looked at the photographs of the cast? Notice the row of chorus girls who are supposed to be expressing fear. Their attitudes are so mechanical that the attempt is ridiculous. Notice the picture of the “star” expressing the same emotion: his muscles are drawn, his eyebrows lifted, he shrinks, and fear shines through his eyes. That actor felt fear when the photograph was taken. The chorus girls felt that it was time for a rarebit, and more nearly expressed that emotion than they did fear. Incidentally, that is one reason why they stay in the chorus.

The movements of the facial muscles may mean a great deal more than the movements of the hand. The man who sits in a dejected heap with a look of despair on his face is expressing his thoughts and feelings just as effectively as the man who is waving his arms and shouting from the back of a dray wagon. The eye has been called the window of the soul. Through it shines the light of our thoughts and feelings.

Do not use too much gesture

As a matter of fact, in the big crises of life we do not go through many actions. When your closest friend dies you do not throw up your hands and talk about your grief. You are more likely to sit and brood in dry-eyed silence. The Hudson River does not make much noise on its way to the sea—it is not half so loud as the little creek up in Bronx Park that a bullfrog could leap across. The barking dog never tears your trousers—at least they say he doesn’t. Do not fear the man who waves his arms and shouts his anger, but the man who comes up quietly with eyes flaming and face burning may knock you down. Fuss is not force. Observe these principles in nature and practice them in your delivery.

The writer of this chapter once observed an instructor drilling a class in gesture. They had come to the passage from Henry VIII in which the humbled Cardinal says: “Farewell, a long farewell to all my greatness.” It is one of the pathetic passages of literature. A man uttering such a sentiment would be crushed, and the last thing on earth he would do would be to make flamboyant movements. Yet this class had an elocutionary manual before them that gave an appropriate gesture for every occasion, from paying the gas bill to death-bed farewells. So they were instructed to throw their arms out at full length on each side and say: “Farewell, a long farewell to all my greatness.” Such a gesture might possibly be used in an after-dinner speech at the convention of a telephone company whose lines extended from the Atlantic to the Pacific, but to think of Wolsey’s using that movement would suggest that his fate was just.

Posture

The physical attitude to be taken before the audience really is included in gesture. Just what that attitude should be depends, not on rules, but on the spirit of the speech and the occasion. Senator La Follette stood for three hours with his weight thrown on his forward foot as he leaned out over the footlights, ran his fingers through his hair, and flamed out a denunciation of the trusts. It was very effective. But imagine a speaker taking that kind of position to discourse on the development of road-making machinery. If you have a fiery, aggressive message, and will let yourself go, nature will naturally pull your weight to your forward foot. A man in a hot political argument or a street brawl never has to stop to think upon which foot he should throw his weight. You may sometimes place your weight on your back foot if you have a restful and calm message—but don’t worry about it: just stand like a man who genuinely feels what he is saying. Do not stand with your heels close together, like a soldier or a butler. No more should you stand with them wide apart like a traffic policeman. Use simple good manners and common sense.

Here a word of caution is needed. We have advised you to allow your gestures and postures to be spontaneous and not woodenly prepared beforehand, but do not go to the extreme of ignoring the importance of acquiring mastery of your physical movements. A muscular hand made flexible by free movement, is far more likely to be an effective instrument in gesture than a stiff, pudgy bunch of fingers. If your shoulders are lithe and carried well, while your chest does not retreat from association with your chin, the chances of using good extemporaneous gestures are so much the better. Learn to keep the back of your neck touching your collar, hold your chest high, and keep down your waist measure.

So attention to strength, poise, flexibility, and grace of body are the foundations of good gesture, for they are expressions of vitality, and without vitality no speaker can enter the kingdom of power. When an awkward giant like Abraham Lincoln rose to the sublimest heights of oratory he did so because of the greatness of his soul—his very ruggedness of spirit and artless honesty were properly expressed in his gnarly body. The fire of character, of earnestness, and of message swept his hearers before him when the tepid words of an insincere Apollo would have left no effect. But be sure you are a second Lincoln before you despise the handicap of physical awkwardness.

“Ty” Cobb has confided to the public that when he is in a batting slump he even stands before a mirror, bat in hand, to observe the “swing” and “follow through” of his batting form. If you would learn to stand well before an audience, look at yourself in a mirror—but not too often. Practice walking and standing before the mirror so as to conquer awkwardness—not to cultivate a pose. Stand on the platform in the same easy manner that you would use before guests in a drawing-room. If your position is not graceful, make it so by dancing, gymnasium work, and by getting grace and poise in your mind.

Do not continually hold the same position. Any big change of thought necessitates a change of position. Be at home. There are no rules—it is all a matter of taste. While on the platform forget that you have any hands until you desire to use them—then remember them effectively. Gravity will take care of them. Of course, if you want to put them behind you, or fold them once in awhile, it is not going to ruin your speech. Thought and feeling are the big things in speaking—not the position of a foot or a hand. Simply put your limbs where you want them to be—you have a will, so do not neglect to use it.

Let us reiterate, do not despise practice. Your gestures and movements may be spontaneous and still be wrong. No matter how natural they are, it is possible to improve them.

It is impossible for anyone—even yourself—to criticise your gestures until after they are made. You can’t prune a peach tree until it comes up; therefore speak much, and observe your own speech. While you are examining yourself, do not forget to study statuary and paintings to see how the great portrayers of nature have made their subjects express ideas through action. Notice the gestures of the best speakers and actors. Observe the physical expression of life everywhere. The leaves on the tree respond to the slightest breeze. The muscles of your face, the light of your eyes, should respond to the slightest change of feeling. Emerson says: “Every man that I meet is my superior in some way. In that I learn of him.” Illiterate Italians make gestures so wonderful and beautiful that Booth or Barrett might have sat at their feet and been instructed. Open your eyes. Emerson says again: “We are immersed in beauty, but our eyes have no clear vision.” Toss this book to one side; go out and watch one child plead with another for a bite of apple; see a street brawl; observe life in action. Do you want to know how to express victory? Watch the victors’ hands go high on election night. Do you want to plead a cause? Make a composite photograph of all the pleaders in daily life you constantly see. Beg, borrow, and steal the best you can get, BUT DON’T GIVE IT OUT AS THEFT. Assimilate it until it becomes a part of you—then let the expression come out.