Orlando and Oliver studied philosophy together 30 years ago. Their shared love for philosophy, design, and technology reunited them to discuss AI and the future. This month, their exchange appeared in the Lucerne School of Art and Design magazine, where Orlando serves as Vice Dean and lecturer.

Prof. Dr. Orlando Budelacci is the author of Human, Machine, Identity, Ethics of Artificial Intelligence.1 His questions and comments are in bold throughout their discussion. Oliver Reichenstein, the founder of iA Inc., answered his questions from the practical point of view of an interaction designer.

Orlando: You’ve developed successful tools for creatives, the iA Writer for writing and the iA Presenter for presentations. These applications are quite unlike the conventional Microsoft products. Where do you see the differences? Why did you decide to strike out on a completely different path?

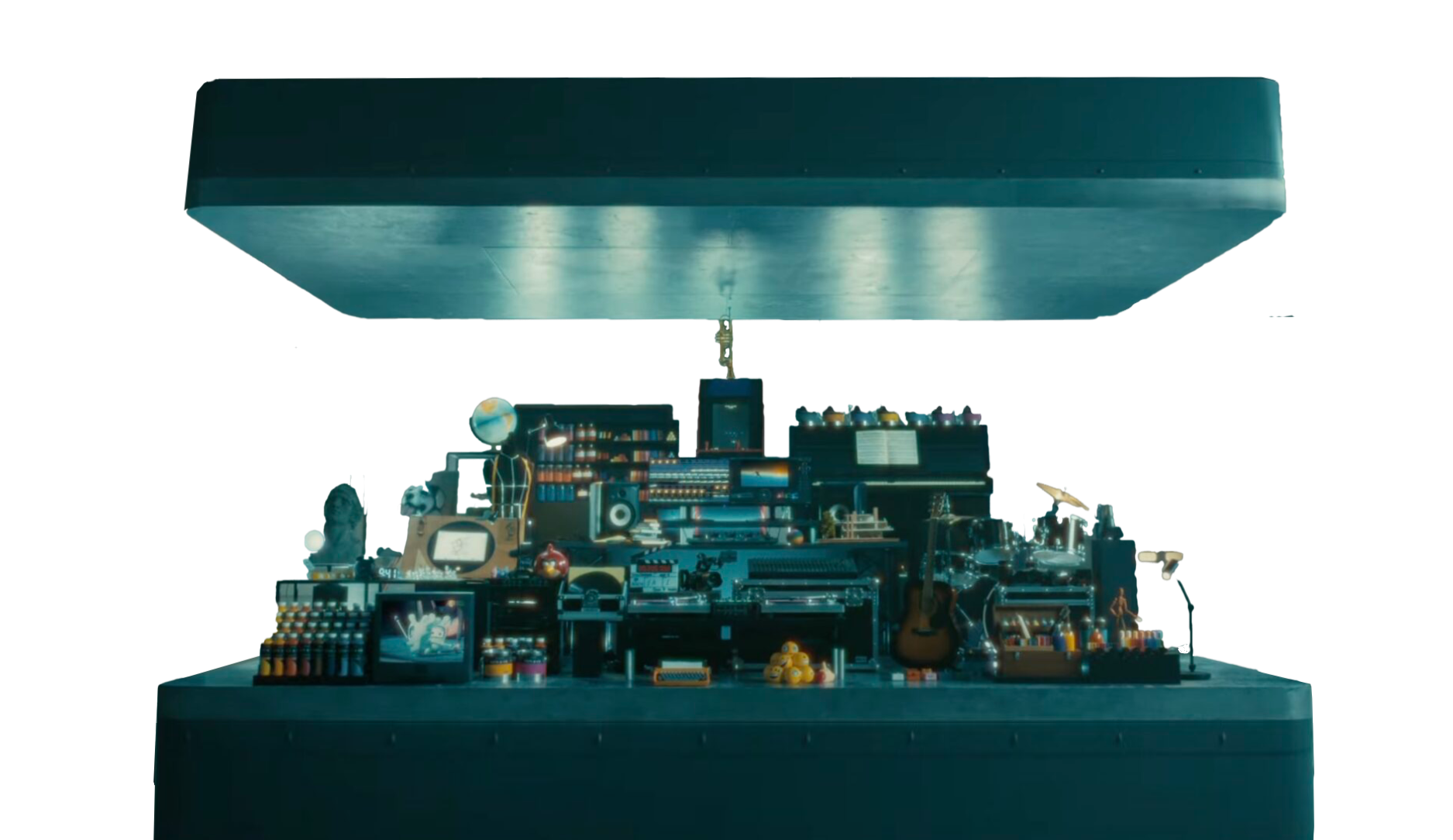

Oliver: Microsoft dominates the productivity software market and does everything it can to consolidate that dominance. We wanted to develop a tool for writing that could only be used for writing. So we based it on the typewriter. It could hardly be more different from Microsoft Word. No buttons, no macros, no frills. In iA Writer, you have no choice but to think and write.

For me, there’s also a certain radicality in that. The Latin word radix means the root of something, its basis, a starting point for further development. You take things back to their roots, and the roots are found in simplicity. You wipe the slate clean, you eliminate intrusive or disruptive elements, anything that might distract from writing. Would you say you have a radical approach to design?

We want to think about things in new, different, better ways. We want to leave all the old stuff behind. We want to design liberated and liberating products. Radicality in design runs the risk of being authoritarian, as in: I’m the designer and I’m going to tell you how it’s going to be. At the same time, good design presupposes a degree of radicality.

We have to ask fundamental questions about the way our products work if we want to make them better. When designing for a display, for instance, we have to keep going back to physical basics. We ask ourselves what’s actually being done here? What’s the aim? How do we achieve it? If you want to surpass expectations, you have to be willing to start by questioning the existing expectations.

So you’re all about the people who need to concentrate on the essentials—when they’re being creative, when they’re thinking, when they’re telling stories, during a presentation. You believe in our capacity for creativity even though machines can already do so much.

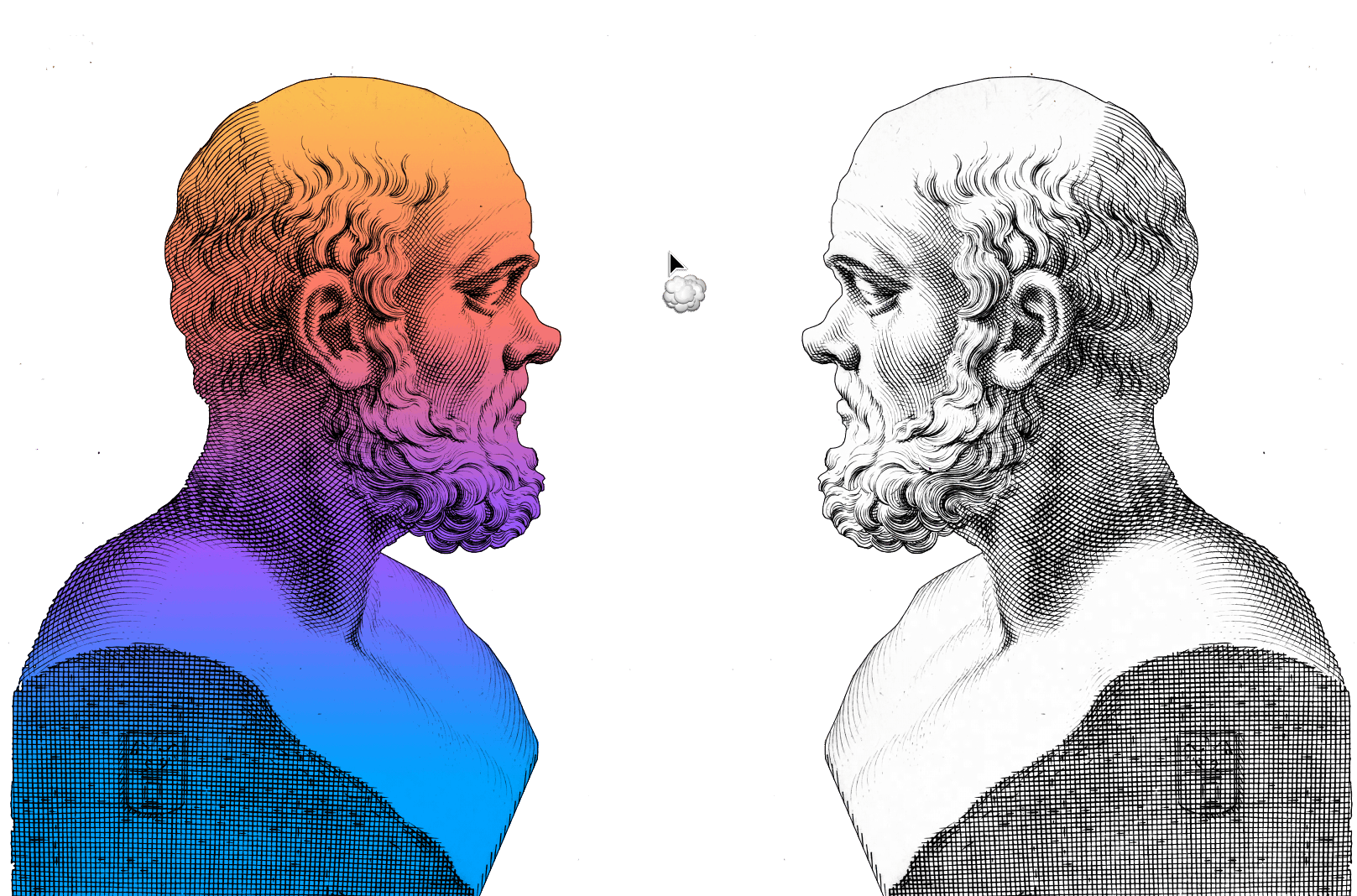

When we’re able to focus on it, work can be a real pleasure. Design requires a willingness to make a fool of yourself by asking outrageous and offensive questions and to be amazed at things that seem perfectly normal to other people. And this willingness is a precondition of philosophy. The untamable Diogenes in his tub, Socrates with his impertinent questions, Wittgenstein with his curious examples…

We make fools of ourselves when we draw people’s attention to perfectly normal matters, to the things we all take for granted even though we wouldn’t take them for granted if we took a closer look at them. We don’t shy away from using strange words, asking curious questions, or doing wild things.

When I was a philosophy student, I used a photocopier to enlarge pages of books onto A3 paper. It helped me understand difficult texts by slowing me down, and it left room for my notes. My classmates thought it was ridiculous, but it helped.

I’ve also noticed that I can’t do final editing from a screen. There seems to be some relationship between the blank space on the page and the possibility of thinking.

And it’s always helpful to read what you’ve written in another form. When you change the typeface, it’s almost like you’re seeing everything through fresh eyes.

I find it interesting that you understand design as the result of reflection and significant mental effort, as a process that starts with thinking. Not something with a beautiful surface, though that might be the end result. It takes significant mental effort to understand precisely what sort of interface you need between the person and the machine, if I understand you correctly. Thinking is the first tool you use when you start designing.

The architect Peter Zumthor says that, as an architect, he’s been working with the concept of space his whole life, and yet (or perhaps for that very reason) he’s increasingly unsure about what space actually is.2 I have the same issue with form as a general notion. If I resist that peculiar sense of exasperation, I’d say that I understand form as an interface.

When we look at an artifact, whether it’s a glass, a microphone, or a computer, then the form—as an interface between subject and object, space and thing, self and world—speaks to us and defines what the artifact is. We know what things really are because we conceive them; we make and manufacture them in a certain form, with the definite idea that the form signifies and conveys how it’s intended, what it is, what and how it wants to be, what it does, and how it’s used.

On top of all that, form as an interface communicates with us even as we’re using it; it responds to us continuously, while being used and through being used. We create objects that produce their own texts about the world around us. Anyone who designs things knows that we know and understand the things that we’ve created and used ourselves far better than we understand nature.

As a lecturer at our university, I’m interested in what it is that students need to become good designers. You’ve just mentioned two of those elements. On the one hand, thinking is essential. On the other, observation of the world. This derives from the insight that you need to be good at observation to come up with a successful design. You need to be someone who observes processes, understands people, and observes how they move in certain spaces, how they work with objects, how they take hold of objects, and so on.

Anyone who paints or draws knows that the challenge of visual representation goes beyond fingers and motor skills. To paint or draw well, you need to learn to see. Drawing well or painting something well is less about skill and technique than it is about attention and sharpening our perception.

In a way this reminds me of the impressionists, who opened their senses to capture the fleeting moment. They were precise observers of atmosphere, space, light, and color. They exposed their senses to the world.

Letting the world affect you in that way assumes a philosophical attitude of acceptance toward the phenomenon. There’s a moment of astonishment when we really perceive something for the first time; when we perceive a phenomenon in the way it affects us and not as we imagine it. We think: Oh, that’s completely different from what I thought, completely different from how I always thought I’d seen it.

At first we don’t understand what we’re seeing, so we start to question our own perception. We look and we observe closely, we find gaps, see details, and the whole time we’re thinking, How can this be real?

And then we look closer still until we see what we’ve been missing all along, something we’d never seen before because of our preconceptions and their projection. It’s only then that we find the space for design! I actually think design presupposes a specific form of thinking and learning by doing.

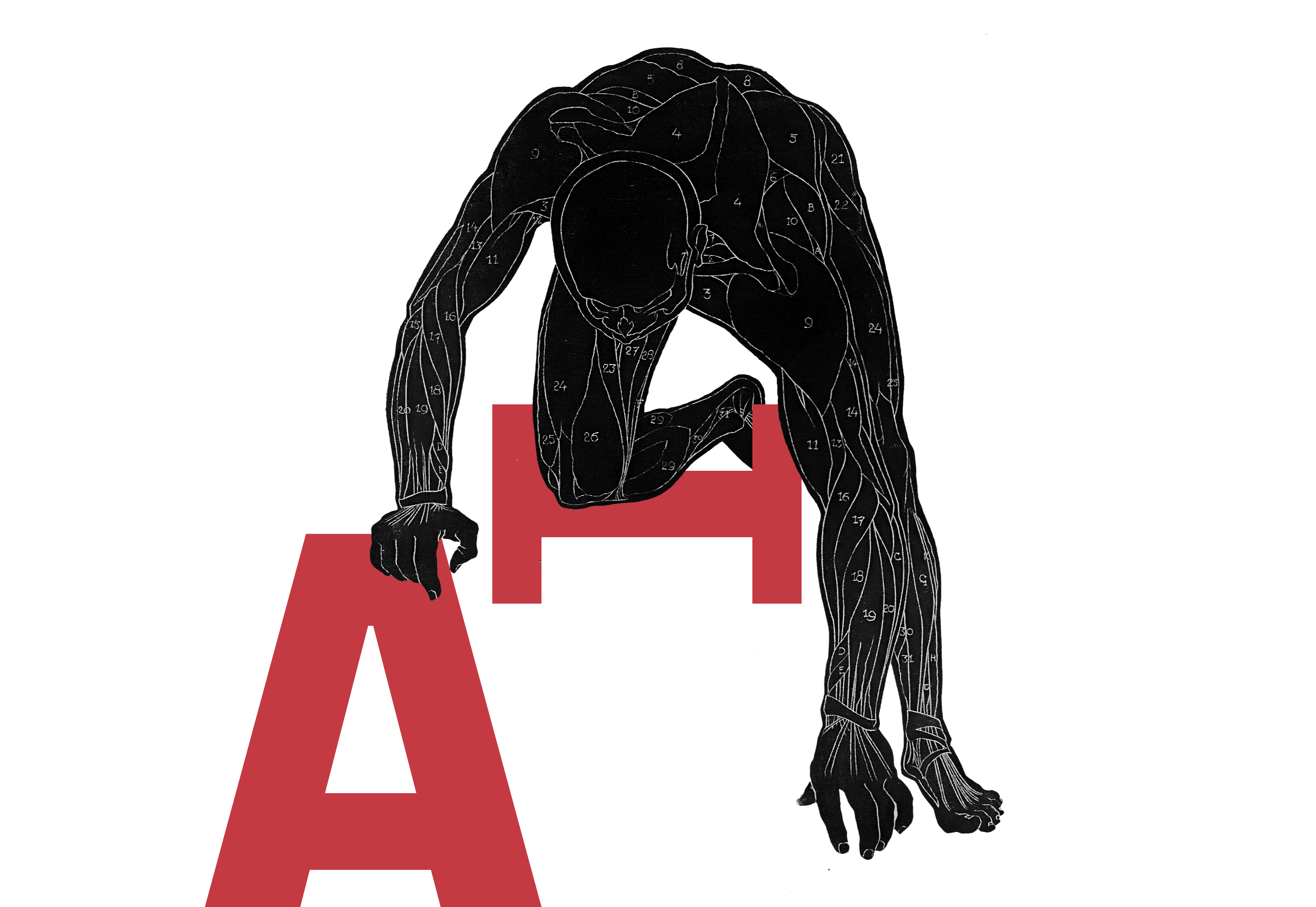

Designing is thinking. Thinking is giving form to indefinite matter. Anyone who thinks gives form to the formless, turns impression into expression.

We live in the turbulent age of the fourth digital revolution. Everyone’s talking about artificial intelligence and it’s causing a lot of consternation. In light of the new technological possibilities, it seems as though thinking and observation are becoming less important. Yet you talk specifically about human capabilities as being essential for a good designer.

I’d like to go back to an observation you made earlier. When I listen to you, I get the impression you want to discover the essence of things through thinking and the honing of human perception. Machines may be able to produce something approximating language, they can generate patchwork images from existing data, but they don’t have dreams, human desires, or imagination. In short, machines are not intelligent. They’re just very good at imitation.

Technology can amplify certain aspects of reality, and it can distort and obscure other aspects. We could use AI to write a book in a couple of minutes—a book that describes nothing real, nothing any person has ever perceived or experienced. Then the book gets published, and thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people spend time reading a statistically calculated string of letters, an alphabetical ornament without any intended meaning, and only then do readers ascribe reality to it—a reality corresponding to what was originally nothing more than the linguistic probability of a sequence of letters. Just gibberish.

Now imagine a million people each spending up to ten hours of their lives investing meaning in this robot gibberish. In purely mathematical terms, if such a non-book defies the odds and goes on to become a bestseller, it wastes several human lives. Books generated by AI and wantonly published without the intervention of any human intelligence are prisons for the mind. But the horrors of AI don’t stop there.

In the final scenario, a couple of generations down the line, books are still being published, but virtually no one reads them anymore. No one thinks written communication has any human substance anymore. Both writing and reading are completely outsourced to AI. Information becomes commercially calculable energy consumption. The planet gets heated up more and more, beyond all tipping points, for nothing.

And this goes on for as long as the money keeps flowing from the virtual pockets of the many to the virtual pockets of the few. We don’t want that. Of course, we don’t! Who wants a future where no one thinks anymore and where money is all that matters? Sadly, we’ve already arrived at that point on a different path, without AI.

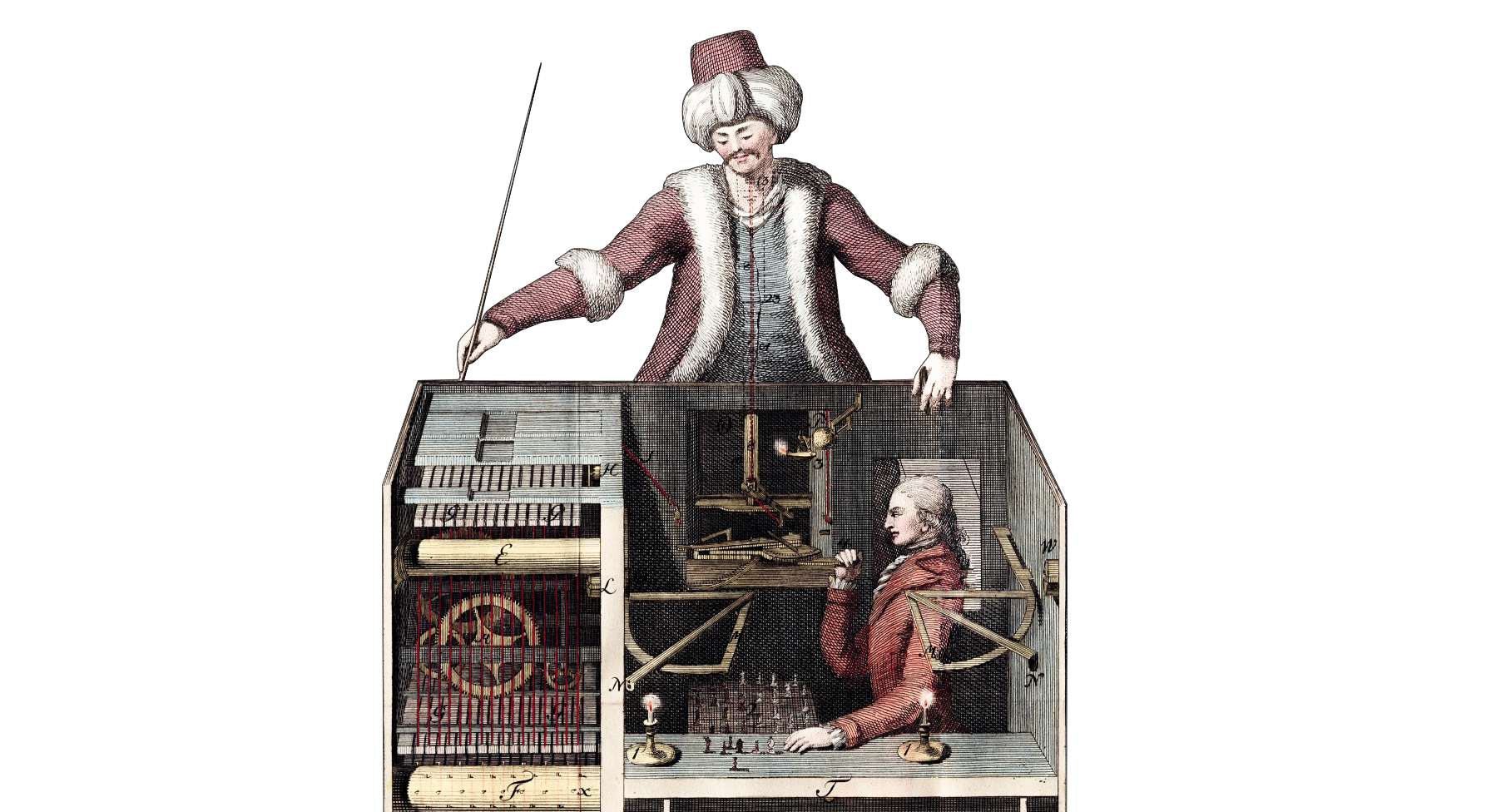

Now, what actually is AI? The Italian philosopher and technology ethicist Luciano Floridi sums it up nicely.3 He posits that AI doesn’t replace our thinking with its own thought. AI, he says, doesn’t think for us. AI doesn’t think at all. AI enables action without thinking. It allows us to perform actions that would previously have required thought. A large language model doesn’t think any more than a pocket calculator or a chess computer thinks.

We’re used to the idea that pocket calculators and chess computers save us the effort of thinking without themselves being capable of thought. It’s no different with a large language model. We just need to get used to the idea that even so-called artificial intelligence, even if it uses words as though it were thinking, doesn’t think.

People sometimes say that technology itself is neutral and that what matters is how it’s used. By this same logic, you can say it’s not the weapon that kills but the person using it. Anyone who designs things knows that the intended use of an object is part of its design. Intention and use can’t be separated from the object without redefining the object. A little kitchen knife with a serrated blade is good for cutting tomatoes. A carving knife is good for carving. You can kill with either, but a bayonet isn’t neutral. The argument that weapons don’t kill is grammatical sophistry.

If you regard artificial intelligence as a tool then its inherent purpose is to make thinking superfluous. First of all, that’s not a particularly helpful position. We could imagine any number of applications that simulate human thinking and get us talking that way. For that, we don’t even need to go as far as we did just now when we were trying to chop tomatoes with a handgun.

I can explore Aristotle, Kant, and Wittgenstein in dialogue with AI. We learn far more through dialogue than we do by monologue. The same goes for simulated dialogue. AI allows us to learn foreign languages in dialogue, which used to be the privilege of a very small minority. AI for learning in dialogue, simulation of thinking and stimulation of thought—I appreciate all these things.

But the danger with AI is that it allows us to perform actions that previously required thought. AI makes actions that require human involvement easy for us; actions such as hiring and firing people, driving cars, and writing books shouldn’t happen without mental effort and emotional involvement.

Instead of just making stuff non-stop we need to learn to think about what we’re going to do, what we’re doing in the moment, and what we’ve done in the past.

Students shouldn’t focus on learning how to be productive with technology; they need to learn how to think about how they use it. Rather than avoiding thinking because it’s stressful, enjoy the freedom that thinking affords. Sport can be painful, yet we know we enjoy it despite the physical exertion.

In the age of AI, it’s more important than ever that we take pleasure in thinking. The purpose of AI is to replace thought. Instead of trying to become more productive, students need to ask themselves questions like: What are the dangers of my interactions with technology? What’s happening to my attention span? How much of what you’ve just written in Word or PowerPoint have you understood? How much of it do you mean? Is that how you feel? Is that what you’ve observed? Do you have any experience of what you’re expressing? And, yes, of course, teachers and parents should be asking themselves the same questions too.

I recently had a conversation with a politician about the risks and opportunities of AI and the consequences of digital transformation. She said it was a matter for schools and legal regulation. I had a very different opinion.

We need to be testing critical thinking and the ability to deal with these new possibilities, and we need to create a laboratory for experimentation. In other words, I’m confident that, with a little critical thinking and enlightenment, people will figure out how best to deal with these new technologies. Ultimately it’s about self-empowerment, which ought to be the aim of education; not paternalism.

Pulling the legislative levers is no guarantee that we’re acting in a morally defensible way. Morality and legality are anything other than congruent. Unfortunately, there’s not a lot of philosophy in the cut and thrust of the industry, which simply looks at what works and what doesn’t.

Careful consideration of grounds for intervention isn’t enough when we’re trying to come up with sensible regulations for everyday practice; we need space to figure out what’s right and what’s not. You can’t just regulate everything, and you can’t just let people get on with it, but you can’t base everything on deliberation either.

As philosophers we’re detached from the world, so we’re far more conscious of that than politicians, who are very much part of it and think they can regulate everything. The politicians’ task is to find the right laws, so they tend to go straight for legislative regulation in every situation. Technicians then stick to these rules or look for loopholes so they can do what they want to do anyway. Then they say: We’re not doing anything illegal, so it can’t be immoral.

Following Immanuel Kant, I’d like to bring in the concept of maturity, which has recently been referred to as “digital literacy”. I assume that people are capable of reflecting on their own prejudices. The possibility of delegating to the law all responsibility for our dealings with technology couldn’t be further from my mind. People bear responsibility for the way they shape the world in their dealings with modern technology. The law is part and parcel of that, but it’s not the central element.

Narcotics are as big a social problem as ever, but most of the parents I speak to now tell me that their biggest problems are phones and games and everything that entails. Those who remain skeptical and circumspect about these extremely powerful technologies, they’re not just nay-sayers.

There are substances that are more or less toxic in and of themselves. Strontium, nicotine, and heroin are toxic even in small quantities. With alcohol, THC, and caffeine, it’s a question of quantity and predisposition. There are comparable dangers in the digital world.

Certain technologies are destructive by design. With other technologies it depends on exposure and use and predisposition. For me, Super Mario is a sugary treat. Even now, when I’m starting a new Super Mario adventure, I have to be careful I don’t overdose and have a sugar crash.

Fortnite is heroin. I can’t stop playing it and it just keeps pulling me in. Instagram is nicotine. TikTok is beer. Threads is boxed wine. Mastodon is THC. Twitter is strontium. There are good things about AI. At the moment it’s being used like opium—to alleviate the pain of thinking.

My sense is that we ought to be promoting critical approaches to the new technological possibilities. Rather than banning them, we should be trying new things without fear of coming into contact with them. What skills do you think designers need to have? What are your priorities when you’re employing new staff?

Designers need to be able to write. To me, writing is the main road to creating, evolving, and transporting design. The majority of our impressions are formulated and expressed through words. Learning to write is a fundamental requirement for design.

It’s surprising that you’re so emphatic about writing being the main road to design. From this, I take it you think language and thinking are relevant to good design. But what I’ve observed at the university is that we have students who are very strong visual thinkers, less so with language.

Photography, graphic design, film, animation—these are all forms of visual language. Of course, you might bring a specific talent to the table, and it may be that you’re better at expressing yourself through music, dance, or animated characters than in words. It may be that our formal sensibilities and the level of non-verbal communication that we achieve in our respective fields lead to the development of certain anxieties about verbal language.

I’m not saying every designer must always be able to write like Schopenhauer, but you need to develop your way of expressing yourself before, during, and after the design process. Design turns impression into expression.

Human expression requires a form of language. Unfortunately, it’s not enough to be adept at drawing, painting, or animation. We need to be able to explain ourselves, market ourselves, and sell ourselves. When you’re formulating verbal language you need to stick close to pre-existing patterns. We need a shared language in order to give expression to our emotions. Without that shared space, others couldn’t translate our expression back into their impression.

In verbal language, this emphatic ability to transform an impression into a comprehensible expression is far more clearly and universally present than it is in visual languages. Understanding how to shape verbal language, from type design to typography, to the emotional, grammatical, and rhetorical shaping of language is one of the main keys to becoming a designer.

Verbal language is universal. We all read, write, and speak. And, unlike when we make films, compose music, or when we paint, we all know how to use words and we all share a much more common space in the use and meaning of words.

In the grand scheme of things, words are always essential to your success. Whatever you express in your articular visual, musical, or physical language, if you want to sell it, you need to learn how to translate some of it into words.

As the teachers, supervisors, colleagues, and friends of designers, it’s our task to make that process less intimidating. The fear of writing is virtually inculcated in us at school. We need to light paths to language for children, we need to awaken the joy of words and writing in them. We need to accept that young people can express themselves freely, willingly, and gladly not just visually but also verbally.

There will, of course, be people who have more or less aptitude in this or that area, but essentially we’re all capable of expressing ourselves perfectly well when we’re relaxed and when we’re talking about something we understand and enjoy.

Algorithms & Imagination., published by the Lucerne School of Art and Design, Ed. Prof. Orlando Budelacci and Jacqueline Holzer. Both Oliver and Orlando studied and majored under Prof. Dr. Annemarie Pieper4, a distinguished figure in practical philosophy who passed away in February, 2024. This exchange between her pupils is dedicated to her memory.

-

Prof. Dr. Orlando Budelacci, Mensch, Maschine, Identität, Ethik der Künstlichen Intelligenz, Basel 2022 ↩

-

“The longer I think about the nature of space, the more mysterious it seems to me.” (“Je länger ich über das Wesen des Raumes nachdenke, desto geheimnisvoller erscheint er mir.”) Peter Zumthor, Architektur Denken, 3rd edition, Basel 2010 ↩

-

“In AI, the outcome matters, not whether the agent or its behaviour is intelligent. Thus, AI is not about reproducing any kind of biological intelligence. It is about doing without it. Current machines have the intelligence of a toaster, and we really do not have much of a clue about how to move from there.” In: Floridi, Luciano. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: Principles, Challenges, and Opportunities, (p. 23). OUP Oxford. Kindle Edition. ↩

-

Annemarie Pieper was a renowned German philosopher and professor of philosophy at the University of Basel. She specialized in ethics and existential philosophy. Her work focused on the ethical implications of modern life and the philosophy of existence. Pieper passed away on February 15, 2024, at the age of 83. She was known for her clear and engaging voice in philosophy, contributing significantly to the fields she studied. Ein weiblicher Sokrates, Annemarie Pieper on Wikipedia ↩