The process is so clear in conference speeches and weblog posts that it is already a stereotype. To get a good perspective on our clients and their users, we start our projects with research. We go mobile first because it naturally gives prioritization, and we want all the content first so we can design in the browser. Yeah, right…

Because “If everyone followed this path, web sites would all be top quality!”, we say. If. Unfortunately, for most of us who do it on a daily basis, the reality of web design follows a different stereotype:

- Make a tree structure

- Photoshop the Home, Section, and Article pages

- Hack on WordPress or one of its cousins

- Fill in the content

- Complain that people are stupid, or evil, or both

Do web projects fail because everybody except us is stupid? Or evil? Or both? Is it because small agencies get small budgets and no time? Because established web designers lie a lot? Because while the layout is great, the content sucks? Because the content is great but the layout sucks?

Or is it because we have 22 drawers full of of comfortable tools, fantasies and excuses to avoid the pain of sitting down and thinking?

Quality

Life and work would be so easy if a lack of quality could be explained in a sentence, and fixed with a better technique. If a website (or any artifact) lacks quality, it is not just one aspect that needs improvement and then it’s all good. Quality is not just the method, just the form, or just the content. The lack of quality doesn’t cumulate in a spot, it is fundamental. Quality is what holds form and content together.

Quality—as in “fitness for purpose”—lives in the structure of a product. A lack of quality is a lack of structure, and a lack of structure is, ultimately, a lack of thought. One does not find a solid structure by following some simple method. We deepen the structure by deepening our thought on the product. Our role as designers is to put thought into things. And that’s why most websites, clients, and jobs suck, and will always suck. Everybody hates to think, because everybody hates to listen, everybody hates to reflect, and we all hate to use our imagination.

Structuring websites is painful because thinking is painful. It is less painful to just rely on a technique. It is less painful to blame the client, the method, or the organization. You can wail about this and make snarky comments as much as you want, but no technique or technology is going to solve a lack of thought. On the contrary! Adding stronger, faster, more technology is going to amplify our thoughtlessness. And that’s why the plastic soup of data we’re fouling our online oceans with is not making us any better at solving tangible problems.

Thought

We avoid the pain of thinking like a medical examination. We’d like to believe we’re too smart to think. Thinking is stressful. While stereotypes click together sweetly, thinking comes in bitter flavors. We recur to clichés rather than reflection, because they make us wise without listening, bright without reasoning, and smart without taking the risk of being imprecise, boring, annoying, wrong. And just like McFood they’re easily bought and quickly swallowed, zero intellectual calories. Just as instinctively as we avoid listening, reflecting, and using our imagination to achieve clarity in writing, we avoid thought when we design websites.

“Wait a minute! Listening is easy, reflection is a great occupation to be paid for, and imagining stuff seems like fun!”, I hear you say. Yes, just like writing seems, romantically, a great occupation, until you sit down and ask yourself: what do I have to say? Once you start seriously listening, reflecting, and trying to use your imagination, you are willingly sitting down for slow, repetitive self-torture:

Listening

Listening is a masochist endeavor. To do it right you have to put everything down. Not just your phone, even pen and paper. There is nothing to hold on to when you just listen. You have to use your full attention, registering everything that you see and hear. You have to slow down your self-perception and focus on the outside, on what you do not understand. Compared to how we usually operate, listening means focusing on pain, diving into boredom. In order to see the other in slow motion, you need to stop the camera of self-perception that makes you the star, and speed up the camera that records the outside.

Listening requires the patience to recognize your feelings in other people’s words, no matter how trivial, dark and empty their language may seem. It requires you to become someone else while you listen. The fog of boredom and emptiness when listening to people you don’t sympathize with can be a sign that they are boring, empty, or not making sense. It can also be a sign that you do not understand. Listening requires that you accept the nuisance of not understanding, of feeling deaf, blind, numb, and still pay attention. Listening is the first step of deep thought. It is painful to give yourself up, but it is highly rewarding. To fill the glass with fresh water, first empty it.

Reflection

Listening, we make ourselves empty and let an outer voice that may torture us with nonsense and banalities take over our mind. Thinking, we follow the same procedure with our inner voice. Thinking is similar to listening. The less we control the voice forcefully, the more it will reveal to us. And yet we have to keep it in check. To think clearly, we make this voice repeat the same annoyances over and over again, at the slowest possible pace. We reflect it upon itself. The first results of our mental milling are raw. We want to believe we intuitively understand things from the start, but this is laziness masquerading as self-flattery. Sharp thinking relies on the logical and linguistic skills, and the intuition that grows with the practicing of these skills. An experienced chess player will ultimately choose their moves relying on intuition. But to win a game, professional chess players need to think several moves ahead. This costs energy. In the 1984/85 World Championship between Kasparov and Karpov, Karpov lost 10kg over the course of 48 games. In extreme situations, grandmasters can think 10 full moves ahead. Most of us amateurs can barely manage four half moves.

A passionate thinker is a chess player that gets more focused the greater the complexity on the board. A thinker is a lunatic that continues to reflect until the inner voice says something familiar. Usually, what you find thinking hard is no different to what other people have said before, but in slightly different words. Thinking helps us to more deeply understand what we believed we understood—rarely do we find something truly fresh. It seems silly to spend so much time to achieve almost nothing. That is why people that avoid thinking often believe that it is, if not directly stupid, definitely not a smart pastime (compared to, say, making money).

Imagination

While very few people commit to improving their listening and reflection skills, even fewer have interest in using their imagination. Using our imagination is harder than we’ve been led to believe. The problem is not that it quickly “runs wild”, or that we have “too much imagination”. The problem is that our imagination is so crippled by the fear of making mistakes, it quickly runs after easy patterns, and jumps on stereotypes. Rarely do we give in to stereotypes as happily as when pushed to imagine different ways to see and do things, believing all the while that we’re super-original.

Using our imagination requires the vision to look into the dark, fully awake. It requires the patience to reflect on what we might feel, again and again, until we feel it more clearly. It requires resisting jumping onto the next big idea, the easy way out. It requires concentration, slowness, even madness to dig deeper and deeper, without knowing if you will find anything. It requires us to be relaxed enough to let association grow new ideas, yet master association so it doesn’t take over and deliver us to dreaming.

Using your imagination, as opposed to the common perception of it being an act of happy dreaming, is walking from dusk into absolute darkness. You have to be ready to stumble, fall, bump your head, and still get up, again and again. And the progress we make from using our imagination is so tiny that it seems hardly worth it. And there is no other way to improve thoughts and things. Innovation comes in nano-steps.

Conclusion

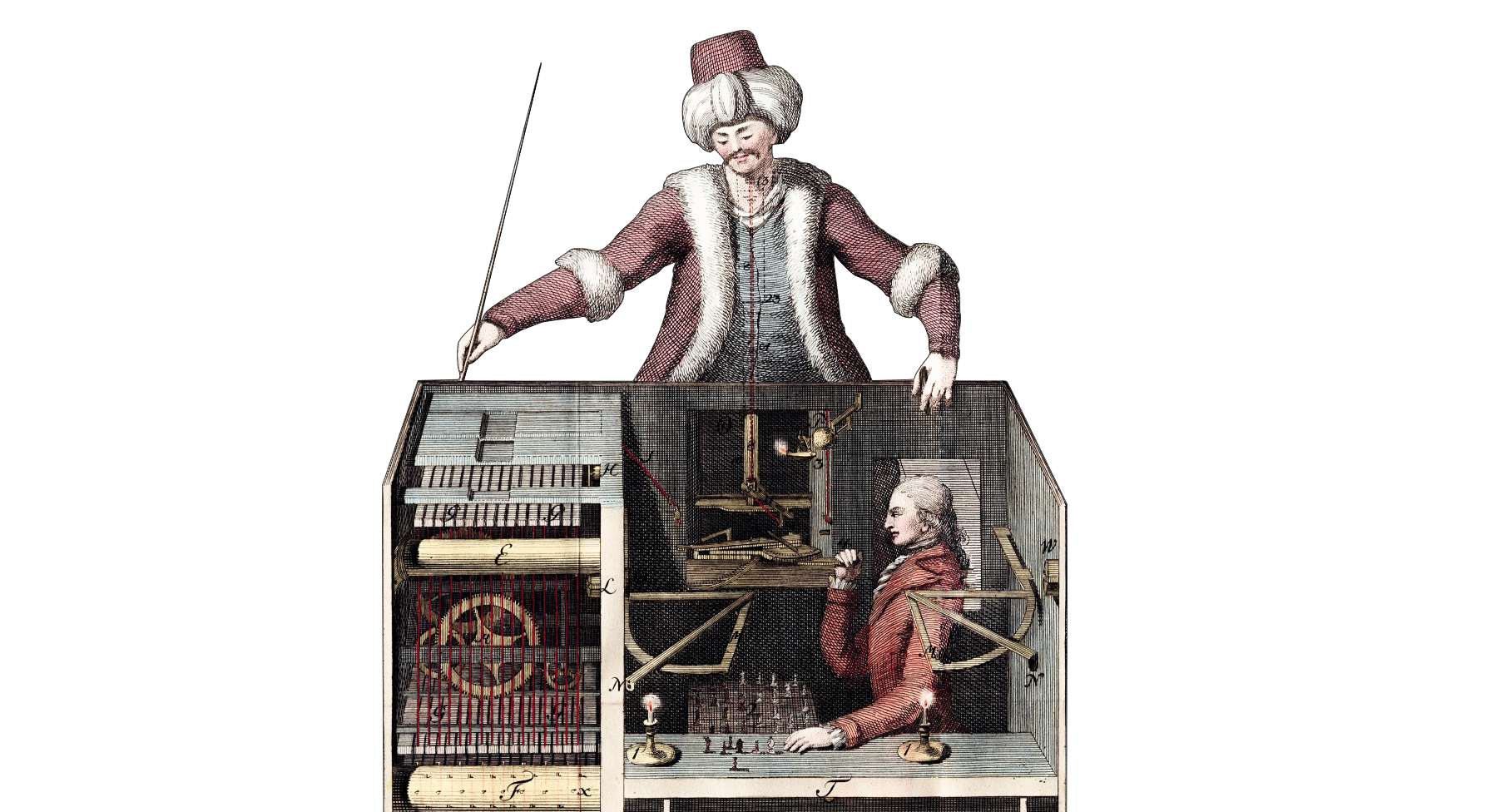

What happens when we create an interface: one mind builds a way for other minds to interact with a thing. To lay the foundation of human-machine interaction you need to put thought into things and that requires that you put things into thought. This is why most interfaces suck, and most interfaces will continue to suck. No model, method, or tool will change that. Thinking is painful.

And there is no best practice, no tip or technique to sort thoughts, to build knowledge systems, and to structure human interaction except for a curious, conscious, vivid mind, guided by a strong will, that resists the temptation to fall back onto fast-thought stereotypes. When building knowledge systems, avoiding thought is a common mistake, and it is programmed failure. Design has little to do with solving a Rubik’s Cube—we don’t work on predefined puzzles.

To move beyond the routines of stereotypical web design, you need to become adept in a wide array of tools and methods, and use the right one at the right time. The more experience you have, the better you will be in choosing your tools. And that includes the decision of which new tools, models and techniques you feel ready to learn. Newer is not better and more is not smarter. But whatever you do, no framework, technique or technology will lessen the pain of thought.

The essential tool with which to build things is your mind. Using and strengthening it hurts as much as using and strengthening other parts of your body. And as you progress, the stretching pain of improvement will stay. Listening costs nerves. Thinking is painful. Using your imagination is walking backwards into a dark and darker tunnel. The ease of following protocol comes with the disappointment of running in circles. The bittersweet pain of progress comes hand in hand with the heartache of making mistakes.

Building structure requires serious listening, serious reflection, and serious imagination. All this requires experience, and no matter how experienced you are, it costs you. We spend our time and nerves to save users their time and nerves. Well-designed things give us the invaluable present of time. Well-designed products do not just save us time, they make us enjoy the time we spend with them. They make us feel that someone has been thinking about us, that a nice person took care of the little things for us. This is mainly why we perceive well-designed things as more beautiful the longer we use them, and the more used they become. A trait that websites lack completely. But that is another story…