You can find plenty of advice on slide design online. Most of it focuses on visual design, transitions, and other decoration. A great presentation isn’t about polished formatting—it’s about how to get your message across.

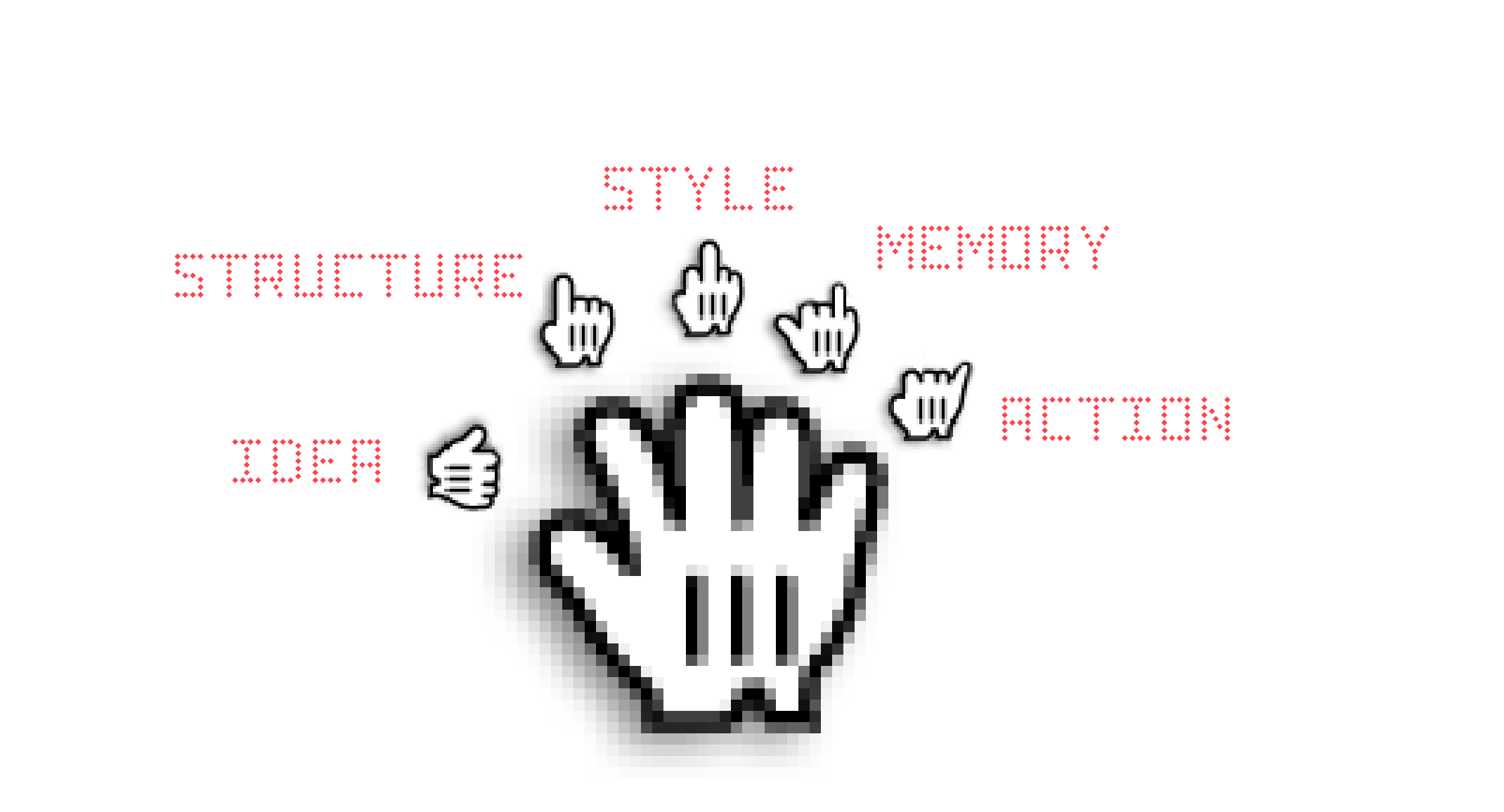

Presenting is an ancient art, studied and refined over centuries, and captured in the Five Canons of Rhetoric.1 These principles offer simple guidelines for the art of clear communication, yet most people today don’t even know they exist. That’s a missed opportunity, as they provide timeless tools to shape and deliver a message that resonates.

These five principles won’t give you a perfect formula—there isn’t one. But they provide a flexible framework to help you create a powerful presentation.

Keep in mind: if your message is weak, no amount of design will save it. The canons are not a checklist but a cycle that guides you through crafting a clear, strong message.

1. Idea

The Thumbs (Up)

The heart of a great presentation lies in the message itself, not in how it looks. As Dale Ludwig and Greg Owen-Boger point out, instead of following rigid formulas, we should focus solely on what we want to say.

When preparing a presentation, it’s never a good idea to begin with a rule. If you do, you’re focusing on the appearance of good delivery and not the effect of it. ―Dale Ludwig and Greg Owen-Boger, The Orderly Conversation.

Focus on the content, not the appearance. Your slides are just visual aids to your storytelling; they are not the essence of your presentation. To captivate your audience, you need a compelling story. Stories create connections. A connection isn’t achieved through stock images, graphs, or bullet points, but through the power of your voice.

They may forget what you said, but they will never forget how you made them feel. ―Carl W. Buechner

Storytelling is key. Like every skill, it is both a gift and something that can be trained. No one is born a good storyteller.

There are some techniques to learn such as plot development, character building, or pacing.2 Studying and observing other presenters is essential for refining your own style.3 Investing time in improving your storytelling skills will be invaluable in many aspects of your life.

Engaging in lifelong learning to improve your public speaking skills is far from drudgery. It can lead to a better job, higher profits, more donations, and public policy objectives. That sounds like fun to me. ―Ed Barks

When preparing a presentation, most of your time should be spent on the story. The design should evolve out of your structure. Focusing on your message is hard with PowerPoint or Keynote because they start with design and constantly remind us to care about it. This is why we created Presenter.

2. Order

Mnemonic: The index finger

After shaping your story, the next step is building the structure. A clear flow keeps your audience engaged. Your structure is the framework. It gives your message order and makes it easy to follow. Without structure, even a great story can lose impact.

2.1 Don’t Worry About the Start, Just Start

There are plenty of ways to start a presentation. You can start with what everyone knows and agrees. You can start with a bang and say something shocking to get people’s attention. Or you can dive right in and pretend that you already introduced yourself. You can introduce yourself humbly and praise the audience (captatio benevolentiae).

When starting to prepare a presentation, don’t worry too much about your first words. Just start. Once you’ve written your story and you know what you will say, the intro will come easily. The best openings come at the end.

2.2 One, Two, Three…

To get started with writing your presentation, pick a simple three-part structure and write your story. You are usually well served by choosing three parts to get started.4 You can (and most likely will) still restructure, delete, add, and move the parts around later.

1. Introduction (Set the Stage)

Start by introducing your key message. Explain the problem or challenge. Show why the audience should care. Keep it short and clear. Give a quick overview of what’s to come.

2. Development (Build the Case)

This is the main part. Present your argument or story. Each point should connect to the next. Make sure your ideas flow logically.

3. Conclusion (Wrap Up)

End by summarizing your key points. Reinforce the core message. Leave the audience with something to remember. Finish strong to make a lasting impression.

2.3 One Idea per Slide

Stick to one idea per slide. Too many ideas on one slide can confuse the audience. Simple slides make your message clearer and easier to remember.

2.4 Logical Flow

Make sure the presentation flows in an order that makes sense. Whether you follow a timeline or a problem-solution format, the audience should always know where they are. Use clear transitions to guide them.

2.5 Repetition for Impact

Repeat key points to make them stick. You can do this through words, visuals, or slides. Repeat, but don’t overdo it. Done well, it helps the audience remember your message.

2.6 Timing and Pacing

Watch your timing. Don’t rush through your points. Let each slide breathe. Make sure your content fits within the time you have. Give your audience time to absorb the message.

2.7 Structure and Restructure

Use the rule of threes to get started. Write the speech first, then optimize, but keep optimizing your structure until it makes sense. But do not shuffle around slides randomly hoping that they somehow make sense. Your slides are not puzzle pieces that can be shifted and turned until they make sense because they were always meant to fit together. You tear the fabric of your speech if structure by trial and error. Think and rethink your structure and adjust consciously.

“Do or do not. There is no try” –Yoda

As you improve, your speech starts feeling more real. Preparing a speech is like working on a design, like cooking, like anything you do for others: You know that you crossed the line from okay to good when it starts feeling like it’s not about you anymore.

A strong structure helps guide your audience. It makes your message clear and keeps them focused. When your structure is tight, your presentation becomes more powerful.

3. Style

Mnemonic: The middle finger, obviously

It’s important that your story, your structure, and the words you pick make sense. So instead of trying to find the right picture, find the right words. Think about the right metaphor before you think about the right picture.

3.1 Find the Right Words

Simplify your sentences and find the right connecting words. The right words are not the loudest and the most flowery ones. Think about your audience. Speak their language. You are not speaking for yourself, you are speaking to those who listen.

3.2. Design

In slide presentations, both words and visuals need a good style. Many slide design mistakes come from too many options in programs like PowerPoint. People without design skills often over-customize their slides, making them hard to read. It’s like a cook adding fists full of spices to a sauce, thinking it will taste more Italian. In the same way, new designers add too many colors, fonts, and effects to their slides. The good news? With iA Presenter, you can set aside all that. It offers only good ingredients—good olive oil, fresh basil, garlic, salt, and pepper are all you need to make a good tomato sauce.

iA Presenter comes with responsive layouts and foolproof themes. Don’t spend time tweaking that template or making a new one. Spend your time saved on what matters: your story.

Your audience won’t remember your bullet list animation and most likely they don’t even care. Talking about bullet points…

3.3 Typography

The fewer words you have on the slide, the less you need to worry about typography. One of the most common feature requests we receive is the revered bullet list–bonus points if they can be revealed with animation!

Avoid Walls of Text

Just like bullet lists, long texts are distracting and will divert your audience’s attention away from your message. On top of that, they dilute your message and overwhelm your audience with information. When tempted to fill a slide with text, think of Dianna Booher when she said: “If you can’t write your message in a sentence, you can’t say it in an hour.” Putting a lot of text on a slide and reading it out to the audience is the #1 presentation killer. Don’t do it.5

The best text slides convey their message as starkly and simply as possible. They do not waste words (or slides) on transitional or introductory points, which can and should be stated orally. This means of course that the slides by themselves will not be intelligible as a handout to someone who has not attended the presentation. ―Barbara Minto

Ensuring that your slides are easy to read is also a matter of accessibility. Audiences with poor eyesight should not struggle to decipher your slide from their seats at the back of the room. As always, less is more.

Careful with Bullet Points

The concept of Death by PowerPoint6 is often attributed to the excessive use of bullets in presentations. Bullet points is where PowerPoint gets its name from.7 Your audience is too busy digesting the information on the slide to listen to you. While they are scanning your list to try to understand it, you are talking in the void.

Bullet lists also contradict the widely accepted concept of “One Idea = One Slide”. When you’re packing separate elements into a single frame, how can you make each of them shine? You cannot. Points introduced with bullet lists will never be as impactful to your audience as if they were introduced on their own.8

3.4 Images

Instead of the bullet list with flashy animation, use meaningful elements that illustrate your point, such as icons, tables, quotes, emphasized words, or even better than all that, pictures. However, good pictures are just as rare–and as valuable–as anything good.

Choose pictures carefully. Images can be technically splendid, with great colors, lighting, and a wonderful landscape. But if they don’t tell a good story they make a lot of noise without adding meaning.9

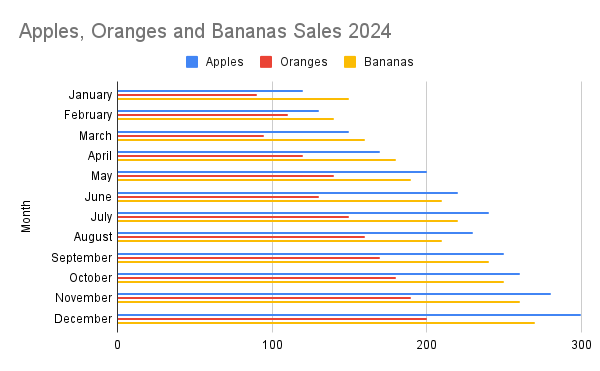

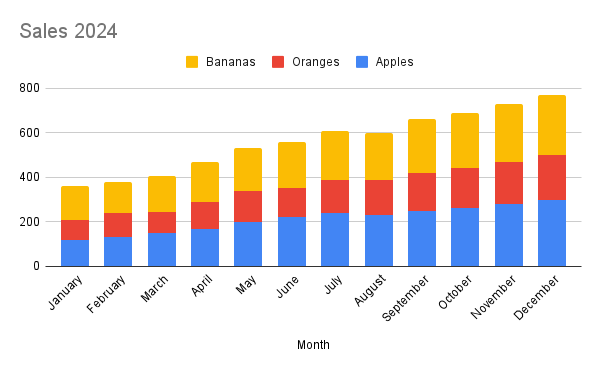

3.5 Charts and Tables

Charts and tables are acceptable as long as they are simple and understandable at a glance—this is not the case for the majority of them. We highly suggest reworking the charts you would like to use to make them as minimalist as possible. Just like for your slides, the most crucial information should be conveyed by you, not read from the slides.

Clear charts, concise visuals, straightforward slides, and plain language. To judge a picture, chart, or any graphic, always ask yourself: Does it tell a clear story or is it just a bunch of boring numbers to pretend that I am serious?

4. Rehearse and Memorize

Mnemonic: The ring finger

Whether it’s a presentation in front of your school friends, a review of the quarterly numbers, or a big TED talk, a good presentation is rewritten, prepared, and rehearsed until it seems natural.

Ideally, you’ll rehearse an important presentation three times from beginning to end. If it still sucks the third time, you’re prepared. You now know what works and doesn’t work. Don’t worry. You’ll be careful and humble enough to just do fine now. Ideally, you know your slides so well that won’t need the teleprompter anymore. You’ll have a backup just in case you get lost.

Along the way, make sure you keep everything, the story, the language, the style, the rehearsing, and the action as simple as possible. As you already know, keeping it simple is easier said than done. Simplicity, is, as Leonardo said, the ultimate sophistication. You can take this tip as an additional weight on your overly complex and confused talk. Or you can see it as a constant motivation to not be afraid to make it simpler. Never be scared to cut slides. Having less material will allow you to speak slowly and clearly.

5. And.. Action

Mnemonic: The little finger—cause it’s easy if you’re prepared

If you manage to simplify, your preparation naturally results in a well-paced presentation where you’re not rushing to finish your slides or, worse, making your audience wait longer to grasp your point.

When deciding between giving a longer or shorter presentation, pick shorter. ‘I wish you had talked longer’ are six words you’ll seldom hear from audiences. ―Sam Harrison

Finish on time and avoid a stressful, incomplete conclusion. Convey only the most important points for them to remember and bring back home. Being afraid to speak in front of a crowd is normal. Everyone, even the most experienced speaker knows that fear in one or the other form.

The way to deal with this fear is to be prepared enough until a part of you is looking forward to present. Be so prepared that you are the person who is most informed on that specific thing you are going to talk about. Don’t be scared to talk to an audience that is willing to listen to you. Enjoy the present of the time they are willing to give you.

Go and Make Nice Things

Changing old habits is challenging. We can see through user feedback how experienced presenters struggle to change their perspective on slide design. In the case of presentations, the pernicious tool of PowerPoint has shaped the content for decades, making it difficult to get out of this frame today. But doing so will be for the best.

Footnote

-

Cicero’s work, especially De Inventione, discusses these canons in detail. Later, Quintilian, another Roman rhetorician, expanded on Cicero’s work in his Institutio Oratoria, further refining and teaching these principles to future generations. Wikipedia, The Five Canons of Rhetoric gives a good overview: “Rhetorical education focused on five canons. The Five Canons of Rhetoric serve as a guide to creating persuasive messages and arguments: 1. Inventio (invention) is the process that leads to the development and refinement of an argument. 2. Dispositio (disposition, or arrangement) determines how an argument should be organized for greatest effect, usually beginning with the exordium 3. Elocutio (style) determines how to present the arguments 4. Memoria (memory) is the process of learning and memorizing the speech and persuasive messages 5. pronuntiatio (presentation) and 5. Actio (delivery) include the gestures, pronunciation, tone, and pace used when presenting the persuasive arguments—the Grand Style. Memory was added much later to the original four canons.” ↩

-

A simple way to improve your storytelling is the “Homework for Life” method of Matthew Dicks. Take 5 minutes at the end of each day to document the stories that already exist in your life. Learn all about this method here. ↩

-

Besides the famous TED Talks, The Moth YouTube channel is another great resource to study storytellers. You can even participate in their Slam competitions if you happen to live nearby. ↩

-

The rule of threes is a basic writing principle. People remember things better when grouped in threes. Try to organize your points into three main ideas. It keeps your presentation clear and memorable. The rule of threes is a good starting point for both the details and the big picture. When you make examples, for instance, try to find three good examples. One is not enough, two is not enough, and four seems exaggerated. When structuring the main parts of your speech or book, start with three main parts. Why three? Because we are used to threes. The Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Beginning, Middle, End. Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis. Like all rules, they are there to get started, and eventually, when it makes sense, you break them. Note: The five canons of rhetoric are five, not three. ↩

-

There are two helpful guidelines to keep you on track: a) 5-5-5: Use a maximum of 5 text lines on a slide, with no more than 5 words in each line, and limiting consecutive slides with this format to only 5 in a row. b) The Billboard: Each slide should be easily readable and understood, similar to information seen while driving past billboards. ↩

-

David JP Phillips in his TED Talk, How to avoid death By PowerPoint, lists all the traps to avoid when making presentations, most of them induced by the general usage made of PowerPoint. A must-watch for anyone who wants to improve their presentation skills. ↩

-

Over time, PowerPoint’s association with bullet points became so strong that the term “Death by PowerPoint” emerged, referring to presentations overloaded with endless slides full of bullet points, leading to viewer fatigue. Despite this critique, PowerPoint’s original purpose of simplifying presentation design, particularly with bullet points, remains one of its core features. In Sweating Bullets: Notes about Inventing PowerPoint, Robert Gaskins explains that the software was built to serve the needs of business professionals who needed to create presentations quickly. Bullet points became central to this process because they organized information in a structured, visually appealing manner: “the great majority of text was in lists of bulleted phrases, not in full sentences.” (p.88), “Presentations often included bulleted lists, and sometimes sub-lists with their own bullets. I chose this as the default format of Presenter’s text box.” (p.96) “Then one morning, when I was taking a shower (where most of history’s great discoveries seem to have occurred), I thought of the name PowerPoint, for no obvious reason. I went in to work and proposed it to other people. No one else much liked it, but I became attached to it. Later that same day, Glenn Hobin, our VP of Sales, returned from a sales trip, and he had an idea for a name: when his plane home was taking off, he had seen out the window along the runway a sign reading “POWERPOINT.” I took his independent discovery as a favorable omen, and we were truly out of time; so I forced the issue, and we sent the name PowerPoint off to our lawyers. Use of the extra internal upper-case letter was mandatory in those days for Mac software, based on Apple’s style in product naming.” (164) ↩

-

Robert Gaskins’ enthusiasm for bullet points could not be stopped by “‘slide Nazis’” who wanted more moderation: “Among all the changes and improvements in PowerPoint 3.0, it was inevitable that many people would suggest new features that would force someone else’s idea of ‘good presentation style’ onto our users. The range of suggestions was amazing. Perhaps users should be prevented from using type smaller than some font size, or type smaller than some fraction of the slide height, or type too small for the typical use of the format (e.g., bigger type for 35mm slides). Or perhaps users should be forbidden from using more than seven bullet points on a single slide, or more than two levels of bullets. Or perhaps users should be prevented from putting more than a dozen boxes on a slide. Or… there was no limit to the ideas of ‘slide Nazis’ for enforcing their own perceptions of good presentation style.” ↩

-

You’ll find more tips to select images for your presentation in this article: A good image tells a good story ↩